There is a general confusion about what language is, what writing is, and the relationship between the two.

Humans have been speaking grammatical languages for hundreds of thousands of years but written representations of spoken language only started appearing 4 to 5 thousand years ago. Even then, for thousands of years, reading and writing was the exclusive domain of a select few—widespread literacy only began to appear perhaps 150 years ago.

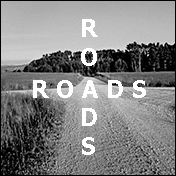

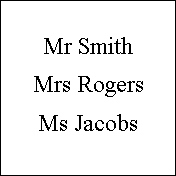

Flip through the pictures and pronounce aloud what is written on each.

‘Speech’ is language, and putting marks on paper to represent spoken words is ‘writing’. Once we have words written on paper we tend to talk about ‘the written language’. But that is a misnomer: the marks on paper we call ‘written language’ have to be visually recognised, then revocalised in the speech centre of the brain before we can extract meaning from them—a far cry from the immediacy of spoken communication. Writing is a secondary modelling system, dependent on a prior primary system, spoken language.1*

Flip through the pictures again. Read each one silently. Concentrate on what is going on as you read.

As you read ‘One good turn deserves another’, you are recognising the words using your eyes. Then there is communication between the visual centre of the brain and the speech areas. You recognise the sign for each letter or the whole word and it is revocalised by the speech centre of your brain as you read.

Note that there is a point where the pure visual recognition becomes ‘meaning’ as the words are revocalised. You can feel/hear the words ‘sounding’ in your brain without any actual sound being made. As you do so you experience ‘meaning’.

With ‘A is for apple’, we recognise a few words, and then encounter a picture. We search for a word beginning with 'A' to match the picture. And because it is a well known phrase most people will read ‘A is for apple’.

The phrase ‘3 + 8 = 11’ consists of symbols that aren't phonetically rendered like written English words. (See sound-symbol.)

There is no phonetic clue in the symbol ‘3’ to indicate it is pronounced

‘th-r-ee’. We recognise the number symbols and the ‘+’ and ‘=’ signs and REMEMBER the word-names for the symbols. Whilst this results in ‘meaning’, there is a secondary understanding (for me) based on the visual symbols alone—thousands of hours looking at written numbers in books and on blackboards!

The rebus for ‘CROSSROADS’ adds an element of puzzle solving, picture recognition and imagination. There is a level of non-verbal understanding of the picture of two roads crossing before we render the puzzle into the word ‘crossroads’, revocalise it and experience a more specific, labelled, ‘meaning’.

What happens when we see the ‘No Smoking’ symbol? We don't necessarily think of the words ‘No Smoking’. We are so familiar with the symbol that we can experience meaning from it without resorting to words. (Similar to the secondary recognition of the number symbols above.)

The honorifics ‘Mr’ & ‘Mrs’ we render as the spoken words ‘Mister’ & ‘Missus’ (from memory—we have forgotten that ‘Mrs’ is an abbreviation for ‘mistress’), but the written symbol ‘Ms’ is a purely graphic symbol—just the first and last letters of ‘Mrs’ and ‘Miss’. No one knows what spoken word to use, because it is a purely written symbol. But vocal renditions are evolving. Currently in Australia the most common pronounciation is /mIz/ as in ‘Les Misérables’.

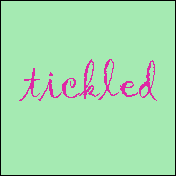

Another rebus—just for fun. After the normal word recognition process for ‘tickled’, the concept of ‘pink’ quickly resolve the puzzle to ‘tickled pink’. Notice the interface between:

These are just my observations as a layman, but it is clear that we take reading for granted without thinking about it.

If you work through the above material slowly, you should emerge with a perception of the reading process:

With this understanding, it is easy to see how the concepts of thought, of words and indeed our perceptions of reality, are affected by literacy, and how cultures without writing can show major differences in mindset. (Ong & Organic Language)

Unlike spoken language, which is the currency of the language centers of the brain, reading is a complicated process. We are dealing with a technology—not a feature of human physical evolution. Often when we read, we only extract a superficial, intellectual perception of meaning. This is why the words illustrated in ‘Organic Language’, (Link), are drawn to connect with the physical sensation of their pronunciation. Although we are ‘reading’ from visual symbols and icons, the shapes and textures involve the body—the drawings are choreographic charts of the ballet that is speech.

* * * * *

1. Ong, Walter J. 1982, Orality and Literacy, Methuen, London, p.8: ‘Written texts all have to be related somehow, directly or indirectly, to the world of sound, the natural habitat of language, to yield their meanings. ‘Reading’ a text means converting it to sound, aloud or in the imagination, syllable-by-syllable in slow reading or sketchily in the rapid reading common to high-technology cultures. Writing can never dispense with orality … we can style writing a ‘secondary modeling system’, dependent on a prior primary system, spoken language. Oral expression can exist and mostly has existed without any writing at all, writing never without orality.’ Back