Index of Content

PARADIGMS OF HUMAN PERCEPTION & CAPACITIES

Medium Daily article 1st Oct. 2022

Many Animals Have Magnetoreception, Now Science is Exploring Whether We Do Too

Humans appear to have the equipment, but can we use it?

Somehow, I’ve lived my entire life without knowing that magnetism is still a mystery. I mean, magnets are everywhere in modern life — they’re in our cell phones, computers, and most technology, as well as hanging on your fridge. Recently experts suggested using magnets to create the air astronauts would require for deep space travel. And yet, the phenomenon remains an enigma.

We know many animals — sea, land, and air — have a sense called magnetoreception, or the ability to sense the Earth’s magnetic field and use it to navigate the planet. But how animals sense it is a matter of ongoing research.

The more I explored the topic, the more I realized how expansive a force magnetism is — not just in modern society but in the animal kingdom and even ancient cultures. Magnetoreception continues to intrigue us, especially since it’s one trait we seem to have missed out on. Or did we?

Earth’s Magnetic Field

I’m sure you know that Earth has a magnetic field that protects the planet from solar and cosmic radiation and prevents our lovely atmosphere from disintegrating. You might also know that this field is the result of enormous amounts of electrically charged molten iron churning near Earth’s core, which creates our planet’s magnetic poles. This planetary magnetic field is called the magnetosphere, and it’s super cool while maintaining a mysterious allure.

The motion of the Earth’s rotation churns the heavy metals in its core while the lighter metals are pushed toward the outer core. Science has a good idea of the ingredients required to create the magnetic field — some kind of conductive fluid, an energy source in constant motion, and something that ignites the magnetic field — but what that "something" is, how it generates a magnetic force, and its origin remains a mystery.

Since the source of Earth’s magnetic field stems from the planet’s core, it encompasses the Earth’s core, mantle, crust, oceans, ionosphere — located between 50 and 600 miles above the Earth’s surface — and the magnetosphere, the outer comet-shaped shield.

The World Magnetic Model (WMM) was created in 1990 as a tool to model changes in Earth’s magnetic field on the planet’s surface (crust) over time, though it’s a continuation of magnetic field mapping efforts dating back to 1701. The WMM is updated and rereleased every five years, the last one was published in 2020, so the next one is due in 2025.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the WMM is the "standard model for navigation, altitude, and heading referencing systems using the geomagnetic field. Additional WMM uses include civilian applications, including navigation and heading systems."

In other words, everything from airplanes to our cellphones or any other system for navigation or tracking uses the WMM.

Though, we aren’t the only ones to recognize and use Earth’s magnetic field for our own purposes. Ancient cultures did too. In my newsletter, I wrote about the Mesopotamian Olmec and Monte Alto’s use of magnetism. It’s remarkable how they incorporated the magnetized portion of stones into their incredible sculptures. I also mention a theory that ancient pyramids were used to focus electromagnetic energy.

Even with our general knowledge of the magnetic field and magnetism, we’ve had to invent technology to use it, whereas many animals evolved to use it through natural ability.

Animal’s Ability to Sense it

I’m sure you know some animals with magnetoreception, such as birds and other migratory animals, sharks, plenty of other marine animals, and molerats who live underground. But did you know dogs, uh, poo in accordance to Earth’s magnetic field?

Needless to say, now that we’ve confirmed magnetoreception is a thing in the animal kingdom, we’re finding it everywhere — even organisms on the microscopic scale are attuned to it.

There’s still plenty of mystery about how magnetoreception works in animals, but there’s also a growing pile of research showing that the range of animals capable of sensing Earth’s magnetic field is broad. Not just the number of animals but the variety of ways those animals are attuned to it.

A dog, for instance, doesn’t pick up on the field the same way trout or birds do. Some animals may feel the magnetic field, while others may actually see it as easily as you see these words before you.

One study on warblers, a type of migratory garden bird, was published in the journal PLoS ONE by biologist Dominik Heyers and his team of colleagues at the University of Oldenburg. For the study, Heyers and his team injected a special dye into the warblers that they could trace as it traveled along the bird’s nerve fibers. They put one type of dye into the eyes and a different kind into an area of the warbler’s brain used to orient itself, called Cluster N.

Heyers and crew discovered that when the birds got their bearing, both dye-types traveled to the warbler’s thalamus — the region responsible for the bird’s vision. This supports previous assumptions that birds use their visual system to navigate and likely see the magnetic field. In an article by National Geographic about the study, Heyers says,

"The magnetic field or magnetic direction may be perceived as a dark or light spot which lies upon the normal visual field of the bird, and which, of course, changes when the bird turns its head."

Although if birds can see the magnetic field from the air, then the field would be like a map, which still doesn’t explain how birds seem to know how to use it or where to go. Then researchers discovered that phytoplankton and bacteria create biological magnetite crystals that sense the planet’s magnetic field.

Now some experts found that at least some birds have these magnetic crystals in their beaks which may work as a sort of compass that helps the birds navigate the magnetic field, like a compass.

Other research studies about magnetoreception in aquatic animals found that many use electromagnetic induction —meaning their bodies are sensitive to electric charges on a cellular or neural level. They convert these signals into magnetic sensitivity.

There’s one more method experts discovered that animals use to sense Earth’s magnetic field. But it involves a bit of a technical explanation involving a biochemical reaction that creates radical pairs — entangled molecules with unpaired electrons.

See, after proteins called cryptochromes are activated by energy absorption, they form radical pairs. Experts believe cryptochromes are crucial to understanding the origin of magnetoreception in animals like birds, which have them in their eyes. But birds aren’t alone. Cryptochrome is an ancient protein that all branches of life have versions of.

Including us.

Can Humans Sense Earth’s Magnetic Field Too?

I could write an entire article about cryptochrome, but I’ll refrain. We, humans, though, have two versions of cryptochrome called — CRY1 and CRY2 — which are sensitive to blue light and help control our circadian rhythm.

In 2011, Lauren Foley from the University of Massachusetts Medical School discovered that CRY2 also senses magnetism after studying Drosophila flies. During her research, Foley discovered that implanting the human version of CRY2 into the flies worked just as well as doubling its own version when repairing their internal magnetic compass.

Some experts point out that while Foley’s research indicates the human cytochrome is capable of functioning as a magnetic sensor, it doesn’t mean that we, humans, can see or sense magnetic fields for one simple reason pointed out in a National Geographic article:

Plugging human cryptochrome into an alien environment like the body of a fly tells you very little about what it does in its native surroundings.

In other words, just because we have the proteins for magnetoreception doesn’t mean we have the equipment — i.e., brain regions or capabilities — to operate or process the trait.

But that’s not the end of our story.

In 2019, biophysicist Joe Kirschvink at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena published a study in eNeuro suggesting that we feel Earth’s magnetic field rather than see it using our visual system like birds.

Kirschvink and his team used electroencephalography (EEG) to record the brain activity of 34 participants in response to changes within an artificial, highly controlled magnetic field equal to Earth’s strength.

They found that rotating the magnetic field prompted a drop in waves of the a frequency, or Alpha — the frequency typical when the brain is at rest while awake. However, the effect only appeared in less than a third of the participants.

The researchers say this could indicate genetic factors, or perhaps past experiences may influence someone’s sensitivity to a magnetic field. What’s curious, though, is that the drop in a frequency only occurred when the magnetic field rotated in a counterclockwise direction — the same direction Earth rotates, along with many other planets and objects in our solar system.

Then again:

In 2000, Klaus Schulten, holder of the UI Swanlund Chair in Physics and professor at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, and doctoral student, Thorsten Ritz, published a paper uniting quantum physics and biology to explain the connections between cryptochrome, light, and magnetoreception.

(Bear with me, if you can’t tell by the last sentence, things are about to get a smidge technical. Skip ahead if you need/want to.)

Schulten and Ritz suggest cryptochrome transfers one of its electrons to a partner molecule called FAD when blue light hits it. The result is particles known as "radical pairs," or unpartnered electrons versus the pairs they usually travel in.

Each electron has a property called "spin," and the spin of radical pairs is linked regardless of whether they spin in the same or opposite directions.

Both states have different chemical properties that the radical pair can switch between. However, the angle of the Earth’s magnetic field can affect these flips and influence the result of the radical pair’s speed or chemical reactions.

An article by National Geographic explains:

This is one of the ways in which the Earth’s magnetic field can affect living cells. It explains why the magnetic sense of animals like birds is tied to vision — after all, cryptochrome is found in the eye, and it’s converted into a radical pair by light.

Though, if Kirschvink and others are right and we feel Earth’s magnetic field rather than visually see it, another issue presents itself. Unlike birds, sharks, turtles, or many other animals, there aren’t really any evolutionary reasons humans would need magnetoreception. In fact, research shows that when there aren’t landmarks around to keep our baring, humans more often wander around in circles…

Perspective Shift

It seems to me that magnetism is a far greater force than we realize. We often attribute great emphasis to things like air, water, and gravity which makes sense since we’re so dependent on them, but magnetism is all around us. And I have a feeling it does and will play a much more significant role than we currently assume.

Then again, when it comes to our ability, or inability, to sense or see Earth’s magnetic field, perhaps it wasn’t always this way. Maybe we used to have magnetoreception back during our hunter-gatherer days and unknowingly used it to migrate along with other animals.

Perhaps we have since evolved the sense away in favor of forming new senses to aid in our shift from hunters and gathers to farmers and industrial workers, and now finally to the digital era.

Or maybe our magnetoreception isn’t gone, but dormant. What if it reactivates when we need it to? Perhaps if future humans move underground! Obviously, I don’t know, I’m no scientist. Still, it’s pretty fun to wonder about.

Katrina Paulson wonders about humanity, questions with no answers, and new discoveries, then she writes about them. Want more? You can find more of her articles in her two newsletters, the free Curious Adventure and the more in-depth version, Curious Life. If you’re not already a Medium member, you can sign up here to read Katrina’s and thousands of other indie writers to your heart’s content.

Subscribing to any option will grant you access to Katrina’s articles and two years of archived content available to you 24/7. Any subscription fees go to helping Katrina pay her bills so she can continue doing what she loves — following her curiosities and sharing them with you.

Thank you for reading. She appreciates you.

Short Articles Index

Internet Archive Index

|

by John Elder

It’s widely held that some people become disturbed when the Moon is full, or even just getting brighter – and a new study suggests that men are affected more than women.

Researchers from Uppsala University in Sweden found that men’s sleep is more "powerfully influenced" by the lunar cycle: They stay awake longer and enjoy less sleep "efficiency" than women when the Moon is in its waxing phase.

During the waning phase, when the Moon rises during the day, the disturbances weren’t demonstrated. In the new study, the researchers used one-night, at-home sleep recordings from 492 women and 360 men.

They found that men whose sleep was recorded during nights in the waxing period of the lunar cycle – during which the Moon becomes brighter and the time at which it is highest in the sky moves from noon to midnight – "exhibited lower sleep efficiency and increased time awake after sleep onset compared to men whose sleep was measured during nights in the waning period".

In contrast, the sleep of women "remained largely unaffected by the lunar cycle". "Our results were robust to adjustment for chronic sleep problems and obstructive sleep apnea severity," said Christian Benedict, Associate Professor at Uppsala University’s Department of Neuroscience, and corresponding author of the study.

The researchers concede that previous studies "have produced somewhat conflicting results on the association between the lunar cycle and sleep, with some reporting an association whereas others did not".

There are several possible explanations for these discrepant findings, including that some of the results "were chance findings". The researchers are confident of their findings because "many past studies investigating the association of the lunar cycle with human sleep did not control their analyses for confounders known to impact human sleep, such as obstructive sleep apnea and insomnia".

During the waxing period, the Moon’s illumination increases and the moment that the Moon crosses a location’s meridian gradually shifts to late evening hours.

In contrast, during the waning period, the Moon’s illumination decreases and the moment that the Moon crosses a location’s meridian gradually shifts to daytime hours.

One mechanism through which the Moon may affect sleep is sunlight reflected by the Moon around times when people usually go to bed.

"Our study, of course, cannot disentangle whether the association of sleep with the lunar cycle was causal or just correlative," Dr Benedict said.

But why men?

In speculating why men are more sleep-disturbed than women during the waxing period, the authors cite a range of studies.

One study reported that blood concentrations of melatonin were lower during the full moon than during the new moon among 20 male subjects.

Another suggested that men are more sensitive to ambient light than women.

In a small study of men this year, blood concentrations of the male hormone testosterone were lower, while those of the stress hormone cortisol were higher, during the full moon compared with the new moon.

Low testosterone and elevated cortisol have been linked with disturbed sleep.

In January, The New Daily reported on a study that found both men and women go to sleep later in the evening and sleep for shorter periods of time as the Moon gets fuller and brighter (in the waxing phase).

The researchers, from the University of Washington, Seattle, suggested that ancient people were essentially programmed to stay awake during the fuller moon, so they could hunt at night.

If that was true, then it might make sense that men – the hunters – be more susceptible to these sleep disturbances.

Short Articles Index

Internet Archive Index

SPIRITUALITY

INTERVIEW WITH THEORETICAL PHYSICIST MARCELLO GLEISER - March 20, 2019

Atheism Is Inconsistent with the Scientific Method: "absence of evidence is not evidence of absence."

Source: Scientific American article.

Atheism Is Inconsistent with the Scientific Method, Prizewinning Physicist Says. In conversation, the 2019 Templeton Prize winner does not pull punches on the limits of science, the value of humility and the irrationality of nonbelief. By Lee Billings.

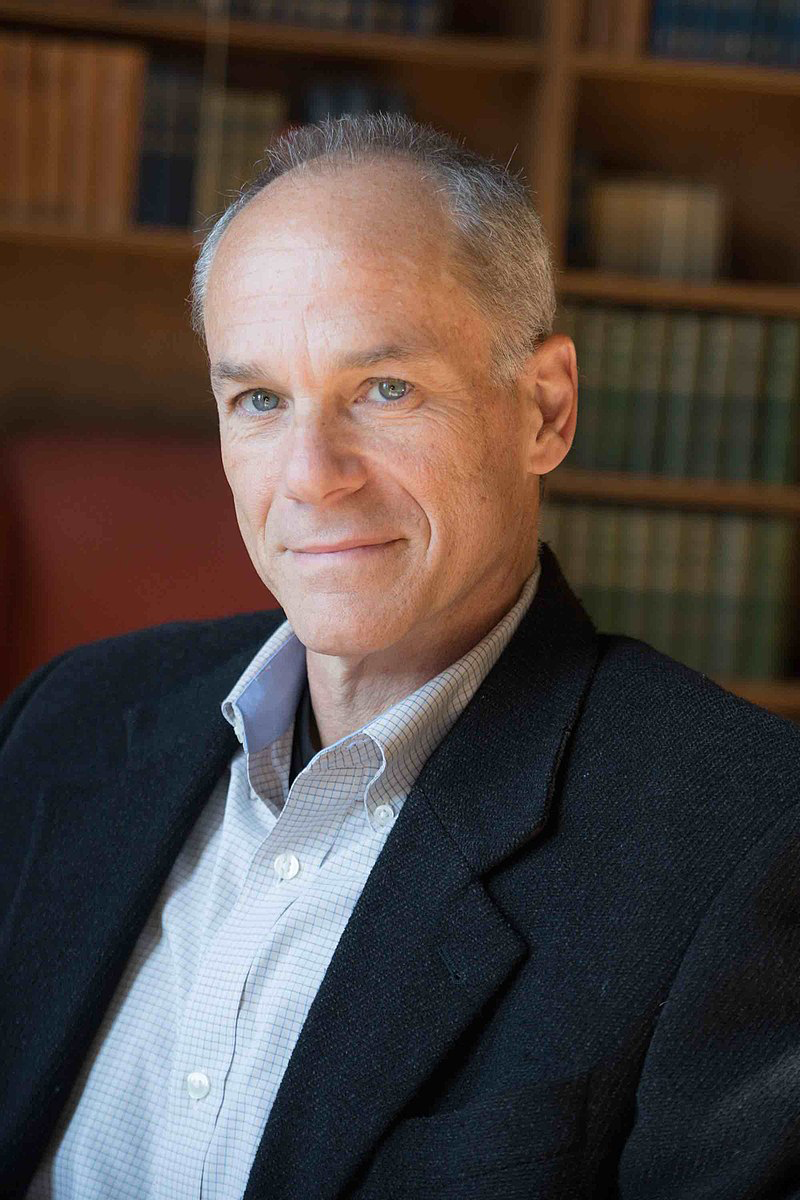

Marcelo Gleiser, a 60-year-old Brazil-born theoretical physicist at Dartmouth College and prolific science popularizer, has won this year’s Templeton Prize. Valued at just under $1.5 million, the award from the John Templeton Foundation annually recognizes an individual "who has made an exceptional contribution to affirming life’s spiritual dimension." Its past recipients include scientific luminaries such as Sir Martin Rees and Freeman Dyson, as well as religious or political leaders such as Mother Teresa, Desmond Tutu and the Dalai Lama.

Across his 35-year scientific career, Gleiser’s research has covered a wide breadth of topics, ranging from the properties of the early universe to the behavior of fundamental particles and the origins of life. But in awarding him its most prestigious honor, the Templeton Foundation chiefly cited his status as a leading public intellectual revealing "the historical, philosophical and cultural links between science, the humanities and spirituality." He is also the first Latin American to receive the prize.

Scientific American spoke with Gleiser about the award, how he plans to advance his message of consilience, the need for humility in science, why humans are special, and the fundamental source of his curiosity as a physicist.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows. ]

Scientific American: First off, congratulations! How did you feel when you heard the news?

Marcelo Gleiser: It was quite a shocker. I feel tremendously honored, very humbled and kind of nervous. It’s a cocktail of emotions, to be honest. I put a lot of weight on the fact that I’m the first Latin American to get this. That, to me anyway, is important—and I’m feeling the weight on my shoulders now. I have my message, you know. The question now is how to get it across as efficiently and clearly as I can, now that I have a much bigger platform to do that from.

You’ve written and spoken eloquently about nature of reality and consciousness, the genesis of life, the possibility of life beyond Earth, the origin and fate of the universe, and more. How do all those disparate topics synergize into one, cohesive message for you?

To me, science is one way of connecting with the mystery of existence. And if you think of it that way, the mystery of existence is something that we have wondered about ever since people began asking questions about who we are and where we come from. So while those questions are now part of scientific research, they are much, much older than science. I’m not talking about the science of materials, or high-temperature superconductivity, which is awesome and super important, but that’s not the kind of science I’m doing. I’m talking about science as part of a much grander and older sort of questioning about who we are in the big picture of the universe. To me, as a theoretical physicist and also someone who spends time out in the mountains, this sort of questioning offers a deeply spiritual connection with the world, through my mind and through my body. Einstein would have said the same thing, I think, with his cosmic religious feeling.

Right. So which aspect of your work do you think is most relevant to the Templeton Foundation’s spiritual aims?

Probably my belief in humility. I believe we should take a much humbler approach to knowledge, in the sense that if you look carefully at the way science works, you’ll see that yes, it is wonderful — magnificent! — but it has limits. And we have to understand and respect those limits. And by doing that, by understanding how science advances, science really becomes a deeply spiritual conversation with the mysterious, about all the things we don’t know. So that’s one answer to your question. And that has nothing to do with organized religion, obviously, but it does inform my position against atheism. I consider myself an agnostic.

Why are you against atheism?

I honestly think atheism is inconsistent with the scientific method. What I mean by that is, what is atheism? It’s a statement, a categorical statement that expresses belief in nonbelief. "I don’t believe even though I have no evidence for or against, simply I don’t believe." Period. It’s a declaration. But in science we don’t really do declarations. We say, "Okay, you can have a hypothesis, you have to have some evidence against or for that." And so an agnostic would say, look, I have no evidence for God or any kind of god (What god, first of all? The Maori gods, or the Jewish or Christian or Muslim God? Which god is that?) But on the other hand, an agnostic would acknowledge no right to make a final statement about something he or she doesn’t know about. "The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence," and all that. This positions me very much against all of the "New Atheist" guys—even though I want my message to be respectful of people’s beliefs and reasoning, which might be community-based, or dignity-based, and so on. And I think obviously the Templeton Foundation likes all of this, because this is part of an emerging conversation. It’s not just me; it’s also my colleague the astrophysicist Adam Frank, and a bunch of others, talking more and more about the relation between science and spirituality.

So, a message of humility, open-mindedness and tolerance. Other than in discussions of God, where else do you see the most urgent need for this ethos?

You know, I’m a "Rare Earth" kind of guy. I think our situation may be rather special, on a planetary or even galactic scale. So when people talk about Copernicus and Copernicanism—the ‘principle of mediocrity’ that states we should expect to be average and typical, I say, "You know what? It’s time to get beyond that." When you look out there at the other planets (and the exoplanets that we can make some sense of), when you look at the history of life on Earth, you will realize this place called Earth is absolutely amazing. And maybe, yes, there are others out there, possibly—who knows, we certainly expect so—but right now what we know is that we have this world, and we are these amazing molecular machines capable of self-awareness, and all that makes us very special indeed. And we know for a fact that there will be no other humans in the universe; there may be some humanoids somewhere out there, but we are unique products of our single, small planet’s long history.

The point is, to understand modern science within this framework is to put humanity back into kind of a moral center of the universe, in which we have the moral duty to preserve this planet and its life with everything that we’ve got, because we understand how rare this whole game is and that for all practical purposes we are alone. For now, anyways. We have to do this! This is a message that I hope will resonate with lots of people, because to me what we really need right now in this increasingly divisive world is a new unifying myth. I mean "myth" as a story that defines a culture. So, what is the myth that will define the culture of the 21st century? It has to be a myth of our species, not about any particular belief system or political party. How can we possibly do that? Well, we can do that using astronomy, using what we have learned from other worlds, to position ourselves and say, "Look, folks, this is not about tribal allegiance, this is about us as a species on a very specific planet that will go on with us—or without us." I think you know this message well.

I do. But let me play devil’s advocate for a moment, only because earlier you referred to the value of humility in science. Some would say now is not the time to be humble, given the rising tide of active, open hostility to science and objectivity around the globe. How would you respond to that?

This is of course something people have already told me: "Are you really sure you want to be saying these things?" And my answer is yes, absolutely. There is a difference between "science" and what we can call "scientism," which is the notion that science can solve all problems. To a large extent, it is not science but rather how humanity has used science that has put us in our present difficulties. Because most people, in general, have no awareness of what science can and cannot do. So they misuse it, and they do not think about science in a more pluralistic way. So, okay, you’re going to develop a self-driving car? Good! But how will that car handle hard choices, like whether to prioritize the lives of its occupants or the lives of pedestrian bystanders? Is it going to just be the technologist from Google who decides? Let us hope not! You have to talk to philosophers, you have to talk to ethicists. And to not understand that, to say that science has all the answers, to me is just nonsense. We cannot presume that we are going to solve all the problems of the world using a strict scientific approach. It will not be the case, and it hasn’t ever been the case, because the world is too complex, and science has methodological powers as well as methodological limitations.

And so, what do I say? I say be honest. There is a quote from the physicist Frank Oppenheimer that fits here: "The worst thing a son of a bitch can do is turn you into a son of a bitch." Which is profane but brilliant. I’m not going to lie about what science can and cannot do because politicians are misusing science and trying to politicize the scientific discourse. I’m going to be honest about the powers of science so that people can actually believe me for my honesty and transparency. If you don’t want to be honest and transparent, you’re just going to become a liar like everybody else. Which is why I get upset by misstatements, like when you have scientists—Stephen Hawking and Lawrence Krauss among them—claiming we have solved the problem of the origin of the universe, or that string theory is correct and that the final "theory of everything" is at hand. Such statements are bogus. So, I feel as if I am a guardian for the integrity of science right now; someone you can trust because this person is open and honest enough to admit that the scientific enterprise has limitations—which doesn’t mean it’s weak!

You mentioned string theory, and your skepticism about the notion of a final "theory of everything." Where does that skepticism come from?

It is impossible for science to obtain a true theory of everything. And the reason for that is epistemological. Basically, the way we acquire information about the world is through measurement. It’s through instruments, right? And because of that, our measurements and instruments are always going to tell us a lot of stuff, but they are going to leave stuff out. And we cannot possibly ever think that we could have a theory of everything, because we cannot ever think that we know everything that there is to know about the universe. This relates to a metaphor I developed that I used as the title of a book, The Island of Knowledge. Knowledge advances, yes? But it’s surrounded by this ocean of the unknown. The paradox of knowledge is that as it expands and the boundary between the known and the unknown changes, you inevitably start to ask questions that you couldn’t even ask before.

I don’t want to discourage people from looking for unified explanations of nature because yes, we need that. A lot of physics is based on this drive to simplify and bring things together. But on the other hand, it is the blank statement that there could ever be a theory of everything that I think is fundamentally wrong from a philosophical perspective. This whole notion of finality and final ideas is, to me, just an attempt to turn science into a religious system, which is something I disagree with profoundly. So then how do you go ahead and left doing research if you don’t think you can get to the final answer? Well, because research is not about the final answer, it’s about the process of discovery. It’s what you find along the way that matters, and it is curiosity that moves the human spirit forward.

Speaking of curiosity… You once wrote, "Scientists, in a sense, are people who keep curiosity burning, trying to find answers to some of the questions they asked as children." As a child, was there a formative question you asked, or an experience you had, that made you into the scientist you are today? Are you still trying to answer it?

I’m still completely fascinated with how much science can tell about the origin and evolution of the universe. Modern cosmology and astrobiology have most of the questions I look for—the idea of the transition from nonlife, to life, to me, is absolutely fascinating. But to be honest with you, the formative experience was that I lost my mom. I was six years old, and that loss was absolutely devastating. It put me in contact with the notion of time from a very early age. And obviously religion was the thing that came immediately, because I’m Jewish, but I became very disillusioned with the Old Testament when I was a teenager, and then I found Einstein. That was when I realized, you can actually ask questions about the nature of time and space and nature itself using science. That just blew me away. And so I think it was a very early sense of loss that made me curious about existence. And if you are curious about existence, physics becomes a wonderful portal, because it brings you close to the nature of the fundamental questions: space, time, origins. And I’ve been happy ever since.

Short Articles Index

Internet Archive Index

The Spiritual Experiences Survey

A copy of an article published by Jules Evans on medium.com 19 Nov. 2022 (link)

In 2016, while working on The Art of Losing Control, I conducted a survey on spiritual experiences. The results were interesting — 85% of participants reported having one or more such experience, but 72% said they thought there was still a taboo around such experiences.

One evening in the winter of 1969, the author Philip Pullman had a transcendent experience on the Charing Cross Road. He tells me:

Somewhere in the Middle East, some Palestinian activists had hijacked a plane and it was sitting on a runway surrounded by police, soldiers, fire engines, and so forth. I saw a photo of it on the front page of the Evening Standard, and then I walked past a busker who was surrounded by a circle of listeners, and I saw a sort of parallel. From then on for the rest of the journey [from Charing Cross to Barnes] I kept seeing things doubled: a thing and then another thing that was very like it. I was in a state of intense intellectual excitement throughout the whole journey. I thought it was a true picture of what the universe was like: a place not of isolated units of indifference, empty of meaning, but a place where everything was connected by similarities and correspondences and echoes. I was very interested at the time in such things as Frances Yates’s books about Hermeticism and Giordano Bruno. I think I was living in an imaginative world of Renaissance magic. In a way, what happened was not surprising, exactly: more the sort of thing that was only to be expected. What I think now is that my consciousness was temporarily altered (certainly not by drugs, but maybe by poetry) so that I was able to see things that are normally beyond the range of visible light, or routine everyday perception.

Pullman has rarely discussed the experience, although it left him with a conviction that the universe is ‘alive, conscious and full of purpose’. He tells me: ‘Everything I’ve written, even the lightest and simplest things, has been an attempt to bear witness to the truth of that statement.’

You could describe that moment as an ecstatic experience — Pullman felt suddenly shifted beyond his ordinary sense of self and reality, and connected to a cosmos alive with meaning and purpose. In his case, it was a spontaneous and unexpected experience, although he was evidently somewhat primed for it by his reading of Renaissance magic. I’m fascinated by such ecstatic experiences. How common are they in modern western culture? Have they become less common as our culture has become less religious and more rationalist? What triggers such experiences today? And how do we make sense of them, if not in a traditional Christian framework?

Spiritual experiences are becoming more common in UK and US, apparently

Research suggests such experiences are, surprisingly, becoming more common in western societies. The Religious Experience Research Centre set up in 1969 by Sir Alister Hardy asked British people: ‘Have you ever experienced a presence or power, whether you call it God or not, which is different from your everyday self?’. In 1978, 36% said yes, in 1987, that had risen to 48%. In 2000, over 75% of respondents to a UK survey conducted by David Hay said they were ‘aware of a spiritual dimension to their experience’. In the US, spiritual experiences are also apparently becoming more frequent — in 1962, when Gallup asked Americans if they’d ‘ever had a religious or mystical experience’, 22% said yes. That figure had risen to 33% by 1994, and 49% in 2009. The Pew Research Centre found last month that a ‘growing share of Americans regularly feel a deep sense of spiritual peace and a sense of wonder’, despite — or perhaps because of — the decline of religious affiliation in the US.

What’s going on? Several possible things. Hay suggested that a ‘deep cultural taboo’ existed against talking about spiritual experiences, because of the negative view of them held by mainstream psychology and psychiatry until recently. That taboo has lessened since the 1960s — psychiatry and psychology are becoming more open to ‘anomalous experience’ and aware they’re not usually pathological (quite the contrary). Culturally, we are becoming more OK about talking about them — one colleague dubs this ‘the Oprah effect’. Both Christianity and spirituality have, since the 1960s, become much more experiential (see the work of Linda Woodhead on spirituality and Tanya Luhrmann on experiential Christianity). We are increasingly suspicious of external authorities — the church, the Bible — and more interested in our own spiritual experiences.

That goes for atheists too. While old-school atheists like Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett or Carl Sagan tended to be suspicious of spiritual experiences and to dismiss them as chemical side-effects, tricks or delusions of the brain, a growing number of atheists and humanists like Sam Harris, Barbara Ehrenreich or Philip Pullman are happy to talk about such experiences and insist on their importance for human flourishing. Indeed, Sanderson Jones, head of the Sunday Assembly (a network of humanist churches), describes his life-philosophy as ‘mystic humanism’.

Results of the survey

I thought it would be fun to do a little amateur survey of my own, using SurveyMonkey. There was a great response, with 309 people filling in my questionnaire. This is obviously a rather selective sample, i.e those who either read my blog, are connected to me on Twitter and Facebook, or are members of London Philosophy Club. Mainly British middle class people, in other words. But the survey attracted a good cross-section in terms of philosophical and religious view points — 25% Christian, 14% agnostic, 24% atheist / humanist, 30% spiritual but not religious. So what did the survey reveal?

Firstly, I asked if people had ‘ever had an experience where you went beyond your ordinary sense of self and felt connected to something bigger than you’. 84% of you had, with 46% of you having such experiences less than 10 times, and a lucky 37% having them quite often. Only 16% said they’d never had such experiences — that rose to 22% for agnostics, 31% for humanists, and 43% for atheists. Those calling themselves ‘spiritual but not religious’ were the most likely to report such experiences, closely followed by Christians. So spiritual experiences seem very common — although there is obviously a self-selecting bias here, as those who aren’t interested in such experiences are less likely to bother with the survey.

I then asked if such experiences happened to you alone or with others, or both. William James and other researchers of ecstasy have thought such experiences usually or always happen to us alone. That’s not the case — only 37% of you say you’ve only had such an experience alone, with 63% saying they’ve had them with others. Ecstatic experiences are often collective.

What are such experiences like? People described all kinds of experiences, but the most common word they used was ‘connection’ and similar words like ‘unity’, ‘at one’, ‘merging’, ‘dissolving’- such words appeared in 37% of people’s descriptions. This tallies with what Dr Cheryl Hunt, editor of the Journal for the Study of Spirituality, told me yesterday at a conference: ‘Connection is the word people use most often to describe such experiences’.

Connection to what? Lots of things. People reported feeling connected to God, to Jesus, the Holy Spirit, angels, to the spirit of deceased loved ones, to the cosmos, to the energy of all things, to nature, to all beings, to humanity, to a loved one, to a group of people, to an animal…or to all of these things. Some examples:

Feeling this deep connection to the earth and to life and to God

feeling of warmth and connectedness with the earth and with other people

I’d taken acid in my 20s. I felt connected to the universe, as though I could understand all of the atoms in the far stretches of the galaxy

Feeling of being surrounded by joyful singing Angels

an overwhelming sense of ‘oneness’

I was in Bangkok surrounded by strange sounds and smells. Bells were ringing. It was quite hot, I was in a rickshaw. Momentarily I felt as though my own spirit had left my body and I became part of everything

i was on the sofa [on ketamine] with a cat on my lap and stroked him endlessly until we became part of the same then both bodies seemed to rush in a tunnel of lights until we were in an open white space where we were suspended and part of everything.

a euphoric sense of loving everyone around me

Feeling at one with the universe, blissful

Standing on the tip of a mountain, watching the snow fall and suddenly feeling a strange sense of expansion and contraction where I became aware of an underlying ‘sameness’ between me, the snow and the mountain

on public transport, surrounded by people I have no connection with, I suddenly get an overwhelming feeling of love for them all

an immense empathy for anyone I met (including animals)

Watching the starry sky, and totally relaxing and feeling this amazingly huge universe is actually home…

When I spend time in deep conversation with one of my children it feels like we move to a higher level of consciousness. Often we will lose track of time and I feel connected to an unknown greater power.

Being very impressed by the sheer fucking scale of the universe and how I was super connected to all of it while at a jazz gig when I was 18 stoned and excited to popping point by the music

Being with a group where people take turns to speak and share authentically and are listened and responded to from the heart….there’s a feeling of surrender to the group

It was in a park. A windy day, and I cut through these magical woods on route and passed a natural pond which was absolutely alive. The wind was in such a direction that it was inspiring all kinds of amazing patterns in the pond. I was mesmerized looking at this and felt in a trance. I felt part of the pond, the wind, the patterns, my thoughts and feelings, the trees, wildlife, and was laughing out in joy.

Sometimes, we get a sense of a cosmic pattern through some strange coincidence, as when Volkonsky finds himself next to his nemesis Kuragin on a field-hospital bed in War and Peace, and ‘ecstatic pity and love for that man overflowed his happy heart’.

Check out this amazing story from the survey:

A month ago in a market in Myanmar I spotted across the vegetable sellers someone who I had tried to avoid meeting in London a city we both live in. This ex girlfriend who had been my ‘best friend’ since childhood betrayed our friendship by having an affair with my husband. She broke up my family and her own and although my husband was also culpable, the misery and guilt killed him prematurely, he had a massive heart attack and died at 55. So I have hated her, and forgiveness was not possible. I spotted her crouching to take a photograph and hid myself, whilst I looked at her. When I went back to my hotel that evening after having a wonderful evening watching the sun setting over the stupas, she was in the foyer with two friends I totally panicked and hid myself again. I watched them take her luggage to a room four doors down from mine. This event shook me coming as it did after a trip across se Asia where I had spent much time contemplating Buddhist teachings and in discussion with monks had thought about forgiveness and anger and attachment. I think this episode was in some way part of a transformative process forcing me to face my demons and let go of my hatred. The next day at breakfast I went down fully prepared to meet her and felt no fear or need to express anything, I felt nothing. She wasn’t there and I didn’t see her again.

You could call these experiences moments of love-connection. People feel expanded beyond their individual ego, ecstatically connected to someone, something, all things, in a way that is joyful, blissful, and loving. Ecstasy seems closely connected to empathy — both are a movement beyond the ego, a love-connection. I asked what triggered such experiences. The most common triggers were nature, the arts (particularly doing or participating in creative practices), and contemplation / meditation. Drugs, romantic love / sex, and proximity to death (yours or someone else’s) were also common triggers. People also gave a lot of their own personal triggers, from cocoa ceremonies to dreams to conversations to dancing the tango.

It’s effing hard to talk about the ineffable

How do people make sense of such experiences? It’s complicated! Only two thirds of you answered this question (it required people to think and write rather than just tick a box) and as a rough categorisation, 24% thought it was God or the Logos (though I didn’t ask what exactly people meant by God), 15% thought it was higher consciousness, 11% thought it was a mystery, 10% thought it was the energy of all things, 9% thought it was neural chemistry, and 3% thought all of the above. But these are very rough categorisations — quite often, people used multiple explanations — God, the energy of all things, nature, all life. People who defined themselves as atheists would still speak of ‘a raised state of consciousness…also perhaps some kind of brief connection to nature / logos’, or ‘a complete ecstatic feeling of oneness with the universe and that everything and I were interconnected’ or ‘a very real connection with the Cosmos’ or ‘Logos / chemical reaction’ or ‘all my atoms responding and resonating with a natural frequency’.

How we interpret such experiences may define whether we call ourselves a humanist, or a Christian, or pantheist, or materialist, and so on. But it is quite a fuzzy area — hard to know, hard to conceptualize, hard to explain. Sometimes people’s interpretations have changed over time. If they are ‘peak experiences’, we meet on the peak, but then streams run down and become separate rivers, valleys, landscapes. But up on the peak, the experiences are often quite similar. And it’s apparent, from the survey, that you don’t like labels, you don’t like being boxed into categories like ‘Christian’ or ‘atheist’. Over a quarter of you refused all such labels, including ‘spiritual but not religious’, and wrote your own ‘other’ down, including: Pyrrhonic sceptic, ‘bit of everything with strong Buddhist and shamanic strains’, ‘bit of Buddhist and Christian but not’, Stoic with Christian roots’, ‘pagan atheist’, ‘goddess feminist’, and my favourite: ‘Christian-Buddhist, Neo-Platonic, Universal agnostic even though I’m a traditional Anglo-Catholic Priest’. Surveys are useful but blunt, their categories don’t always capture the fluxiness of spiritual moments and the cultural identities we incorporate them into.

The fruit

OK, so we’re having more and more groovy spiritual experiences, and we’re not entirely sure what they mean. So what? What are the fruits? I asked how these experiences changed you. Of those who responded (226 of you) the most common way it changed you was to make you feel more connected, to feel ‘the world is my home’, ‘I am a grain of sand in the desert’; to feel more connection and empathy to other beings, a greater sense of compassion and love for them, and also to feel more loved yourself. The second most common way it changed you was to make you more open to a ‘wider sense of life’, it ‘made me open to other ways of looking at things’, it ‘opened the door to wider meanings’, it ‘made me less skeptical, less quick to judge, more compassionate’. It made some of you sense that we are not ‘just’ our brains, bodies or egos. Several of you reported feeling calmer, more ‘centred’, more ‘true to myself’, ‘more me’. It made some of you ‘seek more’, deepen your search, and in some cases led to major behaviour change (‘it pushes me to be a better person…to stay away from alcohol, womanizing and lying’) and major emotional change (‘they allow me to relinquish my desperate control over my negative feelings, either physical pain or mental depression or spiritual guilt. It’s like my well has run dry, but the very last bit of digging uncovered the spring that fills and refills the well of my soul.’) For several of you, such experiences strengthened your commitment to a particular practice — going to church, meditating, praying or, in one case, starting your own spiritual movement (the Sunday Assembly).

For me, the survey gives a fascinating snapshot of a culture that may be abandoning traditional religious affiliation but is still deeply interested in spiritual experiences and religious practices. Although 72% of you agree that ‘there is a taboo against talking about such experiences in western culture’, 80% say they’re happy to talk about them to friends and family, and only 2% say they’d be worried people might think they were crazy — the stigma attached to such experiences is much less than it was 50 years ago.

There is a risk, of course, of spirituality and Christianity becoming too obsessed with experiences — we can fetishize them, become thrill seekers, even addicted to them. Philip Pullman says: ‘Seeking this sort of thing doesn’t work. Seeking it is far too self-centred. It’s like ‘the pursuit of happiness’, which I’ve always thought an absolutely fatuous idea. Things like my experience (and other similar ones) are by-products, not goals. To make them the aim of your life is an act of monumental and self-deceiving egotism. YOU ARE NOT THAT IMPORTANT, but your work might be.’

Alas, most of us haven’t written His Dark Materials. And surely it’s not all about what we produce, is it? I think these moments of deep connection do something important for us and to us. They point beyond the isolated ego, make us feel ‘at home in the world’, and connect us in empathy and love to other beings — so they’re not just good for us, but also for others. And they are not an alternative to commitment, community and practice — they grow out of commitment, community and practice.

But are they just a feeling, or do such experiences give us insights into an actual physical connection between our minds / souls, other beings and the cosmos? Philip Pullman certainly thinks so — he’s one of a growing number of advocates for ‘pan-psychism’, which is the theory that consciousness is a fundamental feature of matter. At the least, we can say that, given how little we understand the nature of consciousness and matter, it’s possible such moments point to something real about the extended mind and its connection to others and to the cosmos. Meanwhile, the real challenge is to take such unusual experiences, and integrate them into ordinary life. To make the extraordinary ordinary and the ordinary extraordinary. In the words of Jack Kornfield, ‘after the ecstasy, the laundry’.

Short Articles Index

Internet Archive Index

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

The Guardian Sep 22, 2021

Adam Morton Climate and environment editor @adamlmorton.

One in five carbon credits under Australia’s main climate policy are ‘junk’ cuts, research finds

‘Avoided deforestation’ projects do not represent genuine abatement, say researchers who liken the Coalition policy to ‘cheap tricks and hot air’

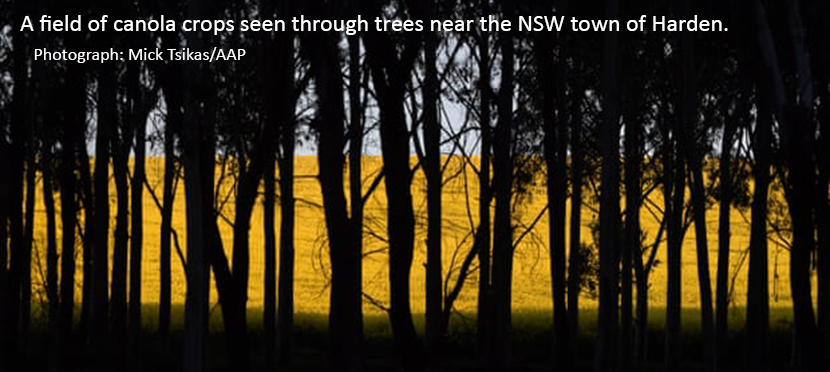

About 20% of carbon credits created under the federal Coalition’s main climate change policy do not represent real cuts in carbon dioxide and are essentially "junk", new research suggests.

The report by the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) and the Australia Institute found "avoided deforestation" projects do not represent genuine abatement as in most cases the areas were never going to be cleared.

The projects involve landholders being issued with carbon credits and paid from the government’s $4.5bn emissions reduction fund for not removing vegetation from their land.

Analysts from the two groups estimated taxpayers had spent about $310m buying more than 26m carbon credits generated through projects unlikely to have helped the climate. The credits had been used to help meet climate targets but in reality were likely to represent "hot air", the report said.

Annica Schoo, the ACF’s lead environmental investigator, said the organisation wrote to government regulators two years ago raising concerns about the integrity of avoided deforestation projects. The Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee launched a review but the results have not been released.

"Our findings demonstrate that the avoided deforestation method – which makes up one in five of all Australian carbon credits – is deeply flawed," she said. "The Morrison government should be embarrassed by its flagship climate policy. Australians want real climate action, not cheap tricks and hot air."

The analysis examined carbon credits issued to landholders in New South Wales who promised not to clear parts of their property. The landholders in question had previously received a state permit to clear certain types of native forest and convert it into grassland or cropland.

Between 2005 and June 2010, the state issued permits giving landholders the green light to clear 2.09m hectares of forest over the subsequent 15 years. Carbon credits were issued to landholders with this type of permit on the assumption all planned to clear their land within the allotted time.

The report found this was implausible as it would have required the state’s rate of land-clearing to increase by at least 750%, and possibly more than 12,000%.

Richie Merzian, the Australia Institute’s climate and energy policy director, said it showed landholders were being issued with credits, and being paid by taxpayers, to retain forests that they could not have cleared had they wanted to. "You would be hard-pressed to find enough bulldozers in the state," he said.

Merzian said the problem was not with the landholders receiving the credits, many of whom were likely to be operating in good faith, but with a system that rewarded an unrealistic number of avoided deforestation projects.

He said a well-designed offsets market would become increasingly important as the country moved towards a net zero target, and called on the emissions reduction minister, Angus Taylor, to "hit pause" on rewarding avoided deforestation projects "until the integrity issues can be resolved". Taylor did not respond before publication.

The ACF-Australia Institute report was criticised by the Clean Energy Regulator, which runs the emissions reduction fund, and the Carbon Market Institute.

A statement from the regulator said it had only had the report for a short time, but it appeared to be "based on some highly questionable assumptions". It said it was not aware of "robust evidence" that the avoided deforestation method was paying to protect land that was never going to be cleared, and it was reasonable to assume farmers with land-clearing permits had intended to clear their property given they had spent time applying for a permit and dealing with "accompanying red tape".

It said farmers did not know they would be eligible for carbon credits when they applied for a land-clearing permit. "The [emissions reduction fund] avoided deforestation projects are preventing land clearing that would otherwise take place," the regulator said.

John Connor, the chief executive of the Carbon Market Institute, which represents businesses that buy and sell credits, said he shared the frustration of the report’s authors about a lack of policy in Australia to drive industrial decarbonisation but he said their analysis contained errors and undermined "credible nature-based climate solutions".

He said he had visited landowners in the state’s west who had permits to clear land but had not used them due to carbon credit revenue. "These are farmers who are not clearing because of this very method," Connor said.

The emissions reduction fund allows landowners and businesses to bid for funding for climate-friendly projects. It has so far operated with limited success in reducing national emissions. The government has paid $831m for emissions cuts and signed contracts for another $1.7bn.

Despite this, national emissions dipped only slightly under the Coalition government before the Covid-19 shutdown. Government data shows the reduction was overwhelmingly due to the rise of solar and wind energy, which are not supported through the fund.

Guardian Australia revealed earlier this year the government had appointed fossil fuel industry leaders to a committee responsible for ensuring the integrity of emissions reduction fund projects.

It is planning to expand the range of projects that can generate carbon credits to include carbon storage, soil carbon, blue carbon (storing CO2 in coastal ocean ecosystems), plantation forestry and biomethane, also known as biogas.

Merzian said the support for avoided deforestation projects from the emissions reduction fund had not slowed the total amount of forest cleared in NSW. Official data showed it had increased for the years covered due to a rise in destruction elsewhere.

Short Articles Index

Internet Archive Index

* * * * *

European Environmental Bureau: 25 April 2022 link

The great detox — largest ever ban of toxic chemicals announced by EU.

Thousands of the most notorious chemicals will be rapidly banned in Europe, the European Commission announced today, as part of the Zero-pollution goal in the EU Green Deal. The European Environmental Bureau (EEB) welcomed the move.

If implemented, the action will be the largest ever regulatory removal of authorised chemicals anywhere and covers chemicals that environmental, consumer and health groups have fought against for decades.

The plan announced today, called the Restrictions Roadmap, is a political commitment to use existing laws to ban all flame retardants, chemicals that are frequently linked to cancer, and all bisphenols, widely used in plastics but which disrupt human hormones. It will also ban all forms of PVC, the least recyclable plastic that contains large amounts of toxic additives, and restrict all PFAS ‘forever chemicals’, plus around 2,000 harmful chemicals found in baby diapers, pacifiers and childcare products.

European officials are unhappy that some 12,000 chemicals known to cause cancer, infertility, reduce vaccine effectiveness and generate other health impacts are still widely found in products, including sensitive categories like baby nappies and pacifiers. Officials consider the roadmap a rapid first step in an EU chemical strategy, with more fundamental changes coming later, notably starting in late 2022.

Some chemicals on the roadmap list were already facing EU restrictions, but most are new. The banning process for all chemicals on the list will begin within two years. All substances will be gone by 2030, the EEB estimates.

Industry raised a "storm of protest" over early drafts of the plans and is expected to try to water them down. Chemicals make up the fourth largest industrial sector in the EU, with firms owned by some of Europe’s richest and most powerful men. Industry association CEFIC acknowledged in December that as many as 12,000 chemicals, present in 74% of consumer or professional products, have properties of serious health or environmental concern.

EU member governments unanimously support the roadmap, although Italy is opposing (see pages 3-5) measures to ban PVC plastics.

The EEB frequently criticises European chemical controls for being too slow and favouring business interests over health and the environment. EEB chemicals policy manager Tatiana Santos said:

“What Von der Leyen’s Commission has announced today opens a new chapter in facing down the growing threat from harmful chemicals. This ‘great detox’ promises to improve the safety of almost all manufactured products and rapidly lower the chemical intensity of our schools, homes and workplaces. It is high time for the EU to turn words into real and urgent action”

An estimated 200,000 chemicals are used in Europe. Global chemicals sales more than doubled between 2000 and 2017 and are expected to double again by 2030. By volume, three quarters of chemicals produced in Europe are hazardous. Scientists recently declared that chemical pollution had crossed a planetary boundary, while last month a UN environment report found that chemical pollution is causing more deaths than Covid-19.

Daily exposure to a mix of toxic substances is linked to rising health, fertility, developmental threats, as well as the collapse of insect, bird and mammal populations. Some 700 industrial chemicals are found in humans today that were not present in our grandparents. Doctors describe babies as born "pre-polluted".

Official polling finds 84% of Europeans worried about the health impact of chemicals in products and 90% about their impact on the environment.

Traditionally, the EU regulates chemicals one by one, an approach that has failed to keep up with industrial development of a new chemical every 1.4 seconds. The EU has banned around 2,000 hazardous chemicals over the last 13 years, more than any other world region. But these restrictions apply to very few products, such as cosmetics and toys. Roughly the same substances will now be banned from childcare items, a larger product group than toys or cosmetics. In addition, most other chemical groups targeted in the roadmap will apply to many product groups, greatly expanding regulatory impact.

The EEB estimates that the roadmap will lead to roughly 5,000 to 7,000 chemicals being banned by 2030.

The roadmap will step up a group approach to regulating chemicals, where the most harmful member of a chemical family defines legal restrictions for the whole family. That should end an industry practice of tweaking chemical formulations slightly to evade bans.

A media briefing with profiles of 6 toxic chemical groups is available here.

For more information:

press@eeb.org

Tatiana Santos, Policy Manager - Chemicals, European Environmental Bureau, tatiana.santos@eeb.org, +32 488 918 597 / +32 2 289 1094

National contacts are available on request.

Short Articles Index

Internet Archive Index

* * * * *

Richard Denniss: Australia’s carbon credits are a joke. Taxpayer money is being wasted on ‘hot air’

|

If a tree doesn’t fall in a forest, was the climate really saved?

Sadly, such esoteric questions have become the main game in the topsy-turvy world of Australian climate policy, where rising emissions from the oil and gas industry are ‘offset’ by not chopping down trees.

The polite term for the creation of dodgy carbon credits is ‘hot air’, but what it really is, is BS.

According to the Morrison government’s greenhouse gas accounts, emissions from burning fossil fuels have risen by 7 per cent since 2005.

But because of all the ‘negative emissions’ from offsets in the so-called land sector, Australia’s ‘net emissions’ are said to be falling.

You don’t have to take my word for the central role of offsetting in Australia’s climate ambition.

According to Senator Matt Canavan: "If we had not stripped the right from farmers to develop their own land, Australia’s emissions would have gone up, not down, in the past 30 years."

According to new research by The Australia Institute and the Australian Conservation Foundation, the Morrison government has committed to spending $310 million to buy carbon credits from landholders in Western New South Wales who promise not to clear their land.

And because the less they promise to do, the more money taxpayers give them, the landholders have promised to do a lot less.

Before the government offered landholders this largesse, they had been clearing an average of 1000 to 2500 hectares of land per year.

But according to the Clean Energy Regulator, which oversees the money handed out from the ‘Emissions Reduction Fund’, the amount of land clearing was about to soar.

Indeed, they assumed the amount of land clearing in Western NSW was about to jump to somewhere between 21,000 and 130,000 hectares per year, and stay at this level for the next 15 years.

An increase of this magnitude is implausible. It is unlikely there are enough bulldozers in Western NSW to get through even the lower bound estimate of the clearing.

And to make matters worse, since the landholders have been receiving the handouts for not clearing, the amount of clearing in the region has increased, not decreased.

The ‘offsetting’ myth

There is no debate about the fact that land clearing is a significant source of carbon emissions.

The trouble with the government’s plan is it is hard to estimate how much clearing landholders were planning to do.

That’s why the actual laws that govern the issuance of carbon credits specifically require calculations to be made using methods that are ‘conservative’ and based on ‘clear and convincing evidence’.

But there’s nothing conservative about the Morrison government regulator’s assumption that land clearing was about to surge by at least 750 per cent, and by up to 12,800 per cent, in Western NSW, and they certainly haven’t provided ‘clear and convincing evidence’ to back up their forecast for the tsunami of tree clearing they say they were expecting.

Of course, it’s not just a lucky minority of landholders who are cashing in on the ERF.

Big polluters like Woodside are desperate to polish up their image by purchasing ‘carbon credits’ so they can ‘offset’ the enormous amount of carbon dioxide and methane their oil and gas production pumps into the atmosphere.

And the looser the rules for creating offsets, the cheaper and easier it is for them to claim they are ‘carbon neutral’.

Buying more hot air is cheaper than selling less gas.

|

Eroding confidence

The Carbon Market Institute criticised the research into the amount of taxpayer money spent buying ‘hot air’ on the basis that it would ‘undermine community confidence in nature-based climate solutions’, and that it is ‘a mug’s game to say what will happen over the next 100 years’.

Truer words have never been spoken, which is of course why the law demands that the calculation of offsets be conservative and evidence based.

But while an industry lobby group defending its industry is no surprise, what is concerning is that the Clean Energy Regulator would not just spring to the defence of the industry it is supposed to be regulating, but would throw red herrings around while they’re at it.

Under the ‘Avoided Deforestation method’ that has been used to left handing out millions of dodgy carbon credits, the abatement is assumed to take place over a 15-year period, but, at the end of that ‘crediting period’, landholders have agreed to protect the carbon stored in the trees they didn’t bulldoze for a further 85 years.

It’s like paying someone to plant trees for 15 years on the condition that, when they finish planting them, they won’t just chop them straight down and sell them for firewood.

The assumption that the trees would be cleared over 15 years underpins the whole method and is relied on in The Australia Institute and Australian Conservation Foundation’s analysis.

The fact the method is based on this assumption should not be controversial: It is detailed in the method, the explanatory statement to the method, and the regulator’s own guidance on the method.

Despite this, the Morrison government’s regulator was as quick as the industry lobbyists to claim that no such assumption exists.

According to the regulator, the method assumes the clearing would occur at some point over the next 100 years. It is unclear if the regulator doesn’t understand its own rules, or simply hopes nobody else does.

No results

Luckily, not all big businesses prefer hot air to climate action.

According to a senior executive of an ASX company quoted in the AFR (link), even though the market for offsets is explicitly regulated by the federal government, there are carbon credits for sale in Australia that reputable businesses "won’t touch with a barge pole".

Due to the failure of the regulator to provide integrity, private companies are spending significant amounts of money on ‘due diligence’ for each offset they buy to distinguish between hot air and genuine abatement.

As The Australia Institute’s Richie Merzian has said, it’s like expecting people to hold each $10 note up to the light to check it’s not counterfeit.

Handing out cheques to people so they don’t do things they were never going to do is obviously problematic – for starters, it borders on fraud.

Beyond the sleight of hand, the biggest issue with Australia’s approach to emission reductions is that it’s just not working.

Actual emissions from electricity, industry and transport are rising steadily in Australia while they are falling rapidly in the UK, the US and the EU.

Storing more carbon in our landscape is a good way to augment efforts to burn fewer fossil fuels, but for many of the offsets being sold in Australia there is more carbon sequestered in the paper the regulator shuffles around than there is in the ‘avoided deforestation’ that has occurred.

You can’t blame polluters like Woodside for wanting to buy the cheapest offsets the government will certify, and you can’t blame their lobbyists for trying to defend them, but we must blame the Morrison government for overseeing a system in which taxpayer and shareholder money is being wasted on hot air.

Richard Denniss is chief economist at independent think tank, The Australia Institute @RDNS_TAI

March '22 article by ANU professor Link

Short Articles Index

Internet Archive Index

* * * * *

Coalition quietly adds fossil fuel industry leaders to emissions reduction panel

Critics ask if some appointees to the Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee have a potential conflict of interest

The Morrison government has quietly appointed fossil fuel industry leaders and a controversial economist to a committee responsible for ensuring the integrity of projects that get climate funding.

Critics have raised concerns about whether some appointees to the Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee may have a potential conflict of interest that could leave its decisions open to legal challenge.

The overhaul of the committee follows the government indicating it plans to expand the industries that can access its $2.5bn emissions reduction fund, including opening it to carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects by oil and gas companies.

The new chair of the committee is David Byers, a former senior executive at the Minerals Council of Australia, BHP and the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association, who now runs CO2CRC, an industry and government-funded CCS research body. He replaced Prof Andrew Macintosh, an environmental law and policy scholar at the Australian National University, who resigned last year.

Byers is joined by the economist Dr Brian Fisher, a former head of the Australian Bureau of Agriculture and Resource Economics who has authored reports warning of the economic impact of emissions reduction targets and been accused of overestimating the cost of combating climate change.

Other recent appointees include Allison Hortle, a petroleum hydrogeologist and research group leader in CSIRO’s oil, gas and fuels program, and Margie Thomson, an agricultural economist and chief executive of the Cement Industry Federation.

A spokesperson for the emissions reduction minister, Angus Taylor, said committee members were "chosen for their skills and experience as required by relevant legislation".

Bill Hare, the chief executive and senior scientist with Climate Analytics, said it appeared the government had appointed "mostly people concerned with the status quo" rather than aiming for a rapid shift towards zero emissions.

He said he was concerned the government planned to allow fossil fuel companies to receive climate funding for merely reducing emissions below inflated estimates of what their CO2 output otherwise might be.

"It really reflects the way in which the government has put fossil fuel interests in front of anything else," Hare said.

How the emissions reduction fund is changing

The committee’s role is to assess whether methods used to earn carbon credits meet offset integrity standards – effectively, that they represent real and new emissions cuts that would not have happened anyway.

Companies that generate credits bid to sell them to the government via the emissions reduction fund for about $16 per tonne of CO2. Most credits have been earned by restoring or protecting vegetation. Some other methods – paying to burn methane emitted at landfill sites and particularly helping mining companies build fossil fuel plants – have proven contentious.

Taylor’s spokesperson said new methods were being developed that would allow carbon credits to be earned from carbon storage, soil carbon, blue carbon (storing CO2 in coastal ocean ecosystems), plantation forestry and biomethane, also known as biogas.

The push to allow CCS projects, which involve capturing emissions before they are released into the atmosphere and injecting them underground, is strongly backed by the oil and gas industry. Santos has said a decision on whether to go ahead with a $1.7bn CCS project at its Moomba gas plant in South Australia hinges on qualifying for carbon credit revenue.

Rod Campbell, a research director with progressive thinktank the Australia Institute, said he believed some of the new appointments should not have been made.

He said in his view Byers had "a clear conflict of interest" as he was paid to run a "CCS lobby group" and the committee would play a role in deciding whether CCS received climate funding.

Carbon credits legislation says Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee members are prohibited from engaging "in any paid employment that conflicts or may conflict with the proper performance of his or her duties".

"The wording of the Act is very clear," Campbell said. "It is completely inappropriate for someone in that position to be overseeing integrity standards. This isn’t carbon capture, its industry capture."

Byers declined an interview request and directed emailed questions to the minister’s office. Thomson and Hortle declined to comment.

In an opinion piece in The Australian in 2019, Byers said a "100% renewables fixation and climate emergency panic" had narrowed the technology options the world was willing to consider.

He argued CCS should be given similar financial support to renewable energy and Australia’s response to climate change should start with a "genuine understanding that carbon management is not about renewables power generation, shifting our motoring fleet to electric vehicles and becoming a nation of vegans".

"It is in tackling the hard challenge represented by low-emissions power generation and transport but also industries such as steel, fertilisers and cement along with our wealth-generating coal and gas export sectors where the true work lies," Byers wrote.

Taylor’s spokesperson did not directly respond to questions as to whether the appointments could lead to potential conflicts of interest.

He said the committee played an important role, made objective decisions informed by robust evidence and analysis, and its members had experience across industry, carbon storage, agricultural science and economics.

The cost of cutting emissions

Fisher is not accused of having a conflict of interest, but several climate market analysts who spoke with Guardian Australia said they were surprised by his appointment given his climate analysis has been politically divisive.

The economist made headlines before the 2019 federal election after suggesting Labor’s climate policies, including its target of a 45% cut in emissions by 2030 compared with 2005, would reduce gross national product over the next decade by hundreds of billions of dollars, lead to lower real wages and employment and substantially increase the cost of electricity compared to what it otherwise would be. He said the Coalition’s less ambitious climate targets would have a lesser economic impact and did not assess the cost of not acting on climate change.

The government cited the analysis while accusing Labor of planning to put a "wrecking ball" through the economy. The then opposition leader, Bill Shorten, said the report should be filed under "P for propaganda". In a piece for Guardian Australia, Frank Jotzo, a climate economist and professor at ANU’s Crawford School of Public Policy, said Fisher’s modelling was based on ridiculous and outdated assumptions and ignored opportunities for cheap cuts.

Fisher this week told Guardian Australia he rejected criticism of his work and said he believed debate over climate action had become too polarised, but noted his 2019 analysis was based on government emissions projections that had since been superseded.

He said he was invited to join the committee based on his role as an author of three assessment reports for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and that his work had also been published in the journal Nature. He said the committee’s role was to ensure emissions reductions were measured "scientifically and appropriately", and he was agnostic about the best way to achieve cuts.

The emissions reduction fund has so far operated with limited success in reducing national emissions. The government has paid $740m for emissions cuts and signed contracts for another $1.66bn. Despite this, national emissions had dipped only slightly since the Coalition was elected in 2013 prior to the Covid-19 shutdown.

Government data shows the small reduction was overwhelmingly due to the rise of solar and wind energy, which are not supported through the fund.

Short Articles Index

Internet Archive Index

POLITICAL CORRECTNESS

Mehreen Faruqi says Human Rights Commission has accepted her racism complaint against Pauline Hanson

The Greens senator made the complaint to the commission over a tweet from the One Nation leader.

Source: SBS News article 9th October 2022.

The Australian Human Rights Commission is set to investigate a racism complaint lodged against One Nation leader Pauline Hanson.

Greens senator Mehreen Faruqi made the complaint following a tweet from Senator Hanson, which said she should “p--- off back to Pakistan”.

On Friday morning, Senator Faruqi's office said the HRC has accepted the complaint.

“People who have been told ‘go back to where you came from’ carry the scars of racism. So many have encouraged me to hold Senator Hanson’s attack to account,” Senator Faruqi said.

“In this day and age, you’d be hard-pressed to find a workplace that would allow someone to racially vilify a colleague without consequence, but sadly Senator Hanson has not been held to account by the Senate.”

READ MORE

Why a tweet from Pauline Hanson could be referred to the human rights commission.

The Greens attempted to censure Senator Hanson in the chamber last month but the motion was amended by the government and opposition to instead condemn all forms of racism.

The tweet from Senator Hanson was posted following comments Senator Faruqi made regarding the death of Queen Elizabeth II.

“Condolences to those who knew the Queen,” Senator Faruqi wrote on Twitter on 9 September.

“I cannot mourn the leader of a racist empire built on stolen lives, land and wealth of colonised peoples.”

Twitter post

Mehreen Faruqi

@MehreenFaruqi

Condolences to those who knew the Queen.

I cannot mourn the leader of a racist empire built on stolen lives, land and wealth of colonized peoples.

We are reminded of the urgency of Treaty with First Nations, justice & reparations for British colonies & becoming a republic.

Senator Hanson's reply to the tweet read: "Your attitude appalls and disgusts me. When you immigrated to Australia you took every advantage of this country.