Common English words such as the verb forms ‘is’, ‘are’, ‘was’ and prepositions ‘up’ and ‘under’, have kept the same meaning for hundreds of years. However, many words, (especially of the classes of adjectives and nouns), tend to take on new meanings over time. (See semantic shift)

If a key word or phrase in a document written, say 200 years ago, has changed in meaning since the document was written, a modern reader may misunderstand the entire document.

An example of this is the phrase ‘the survival of the fittest’. We often hear it given as a justification for unscrupulous or ruthless behaviour in business or politics. The speaker is claiming that ‘the strongest survives’ is a law of nature; that it is the way life has always been; and that their actions are in harmony with the natural order.

Whilst the phrase is believed to summarise Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, it first appeared in Herbert Spencer’s ‘Principles of Biology’ 18641* (five years after Darwin published ‘The Origin of Species’). It did not refer to some aggressive preditor devouring all else, but expressed the idea that when an environment changes, the members of a species that are best suited to the changed conditions are most likely to survive (and reproduce).

Darwin acknowledged the phrase (with reservations), in the 5th edition of his work in 18692*. However, the meaning of the adjective ‘fit’, and hence ‘fittest’, has undergone many changes since the 1860s.

When Spencer used it in 1864 it had the meaning of ‘suited to the circumstances’.3* By the 1890s the adjective was developing an additional meaning of ‘good health’. And throughout the twentieth century, the word continued to accrue attributions of power and strength.

The meaning of ‘fittest’ has changed so much since 1864 that the phrase, ‘the survival of the fittest’, requires translation to be understood in the modern context. A suitable modern translation would be: ‘the survival of the most fitting’.

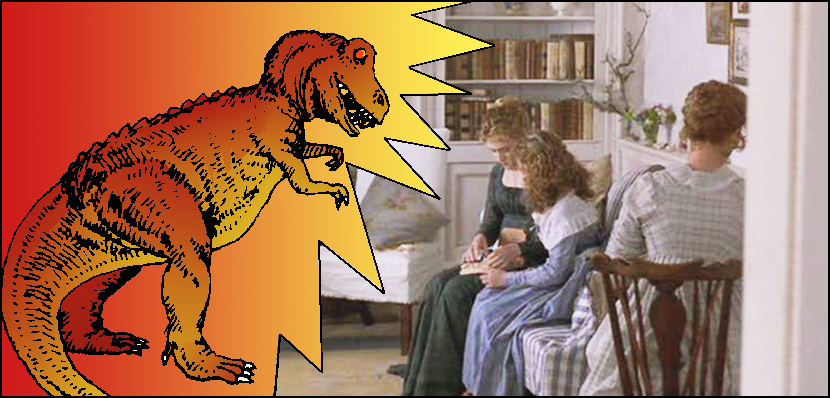

So the image of a predator trampling and killing everything in its environment, changes, (on translation), into an image of of a Jane Austin drawing room with the characters engaging in polite conversation — abiding by social conventions — and ‘fitting in’ with their environment.

1. Spencer, Herbert, 1864, Principles of Biology, William and Norgate, London. p.444

"[§ 164 Talking about changing conditions in an ecosystem] Unless the change in the environment is of so violent a kind as to be universally fatal to the species, it must affect more or less differently the slightly different moving equilibria which the members of the species present. It cannot but happen that some will be more stable than others, when exposed to this new or altered factor. That is to say, it cannot but happen that those individuals whose functions are most out of equilibrium with the modified aggregate of external forces, will be those to die; and that those will survive whose functions happen to be most in equilibrium with the modified aggregate of external forces.

But this survival of the fittest, implies multiplication of the fittest. Out of the fittest thus multiplied, there will, as before, be an overthrowing of the moving equilibrium wherever it presents the least opposing force to the new incident force. And by the continual destruction of the individuals that are the least capable of maintaining their equilibria in presence of this new incident force, there must eventually be arrived at an altered type completely in equilibrium with the altered conditions." Back

2. Darwin, Charles, 1869, On the Origin of Species, John Murray, London (fifth edition) p.72

"Again it may be asked, how is it that varieties, which I have called incipient species, become ultimately converted into good and distinct species, which in most cases obviously differ from each other far more than do the varieties of the same species? How do those groups of species, which constitute what are called distinct genera, and which differ from each other more than do the species of the same genus, arise? All these results ... follow from the struggle for life. Owing to this struggle, variations, however slight and from whatever cause proceeding, if they be in any degree profitable to the individuals of a species, in their infinitely complex relations to other organic beings and to their physical conditions of life, will tend to the preservation of such individuals, and will generally be inherited by the offspring. The offspring, also, will thus have a better chance of surviving, for, of the many individuals of any species which are periodically born, but a small number can survive. I have called this principle, by which each slight variation, if useful, is preserved, by the term Natural Selection, in order to mark its relation to man's power of selection. But the expression often used by Mr. Herbert Spencer of the Survival of the Fittest is more accurate, and is sometimes equally convenient. " Back

3. The Oxford English Dictionary 2nd edition, 1989, Oxford University Press, London

fit (fit), a. ...

1.a. Well adapted or suited to the conditions or circumstances of the case, answering the purpose, proper or appropriate. Cont. for (also, rarely, with ellipsis of for) or to with inf... "

b. absol.; esp. in survival of the fittest. ...

1867 H. Spencer Biol. 193 II. 53 By the continual survival of the fittest, such structures must become established...

6. In Racing or Athletics: In good 'form' or condition; hence colloq. in good health, perfectly well. fit as a fiddle: see fiddle sb. i b.

1869 BRADWOOD The o.v.h. 28 Vale House was not as 'fit' inside as modern conveniences might have made it.

1876 OUIDA Winter City vi. 124 To hear the crowd on a race day call out .. 'My eye, ain’t she fit!' just as if I were one of the mares.

1885 Manch. Exam. 17 Jan 5/5 General Stewart with his men and camels, all apparently well & fit.

1891 DIXON Dict. Idiom and Phr. s.v. Fit 'How are you?' — 'Very fit, thank you, never felt better.' Back