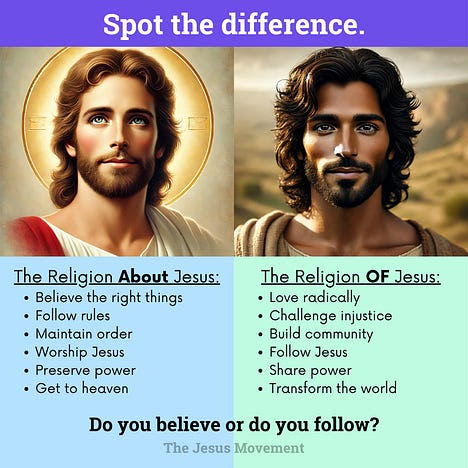

The Religion of Jesus vs. The Religion ABOUT Jesus

There's a big difference between the two

This is a copy of an email posting by Andrew Springer.

Millions of people are turning away from Christianity, and for good reason. What passes for Christianity today would be unrecognizable to Jesus of Nazareth. The religion that claims his name has become, in many ways, the opposite of everything he taught and lived.

Jesus, a poor, Palestinian Jew living under Roman imperial occupation, never intended to start a new religion. His message was far more revolutionary: he showed us how to transform ourselves, our relationship with God, and our world through lives of radical love and resistance to injustice. When we truly follow his way, we don't just change our beliefs—we help build the Kingdom of God here and now.

The great theologian Howard Thurman helped us understand this crucial distinction: there is the religion OF Jesus, and there is the religion ABOUT Jesus.1

What most people think of as Christianity today is the religion ABOUT Jesus—created by the early church, particularly through Paul's writings and later church councils, and developed over centuries by rich, powerful men seeking to maintain their wealth and authority.

This religion ABOUT Jesus emphasizes believing the right things about Jesus's divine nature. It claims he died as a blood sacrifice to appease an angry God.2

It says salvation comes through correct beliefs and that the whole point of faith is to secure a pleasant afterlife. It's about following rules, maintaining order, and preserving existing power structures.

The religion of Jesus himself

But this isn't what Jesus taught or lived. The religion OF Jesus, as Thurman articulated and later theologians like James Cone and Delores Williams expanded upon, is something radically different. As Cone argued, when the religion ABOUT Jesus was co-opted by empire through Constantine, it became "the opposite of what Jesus intended."3

The message of a poor, colonized Jewish man who stood with the oppressed was transformed into a tool of imperial power, a tool of capital, to oppress the working class.

Delores Williams powerfully argued that Jesus didn't come to die or to "conquer death"—he came to show us how to live. His message wasn't about securing a spot in heaven through correct beliefs, but about bringing heaven to earth through correct actions.4

Jesus demonstrated this through what Williams calls his "ministerial vision"—an ethical ministry of words through his teachings and parables, a healing ministry of touch, a militant ministry against evil and oppression, a ministry grounded in faith, a ministry of prayer and contemplation, and above all, a ministry of compassion and radical love.

The greatest commandment, not suggestion

The religion OF Jesus is centered on what Jesus himself declared was most important—loving God with all our heart, soul, and mind, and loving our neighbors as ourselves.

This Greatest Commandment isn't a suggestion—it's the core requirement of following Jesus.5 It's about living a life of radical, inclusive love. It's about standing with the oppressed and marginalized. It's about challenging unjust systems and structures. It's about creating beloved community here and now.

As Thurman taught, Jesus understood what it meant to have "his back against the wall." He lived under Roman imperial rule, faced constant threats of violence, and was ultimately executed by the state. His message was for others in that situation, showing them how to maintain their humanity and dignity while working to transform the systems that oppressed them.

The religion OF Jesus is fundamentally incompatible with systems of oppression like white supremacy, patriarchy, and exploitative capitalism. Jesus's message was so threatening to the powers of his day that they killed him for it. Yet the empire that killed him would later co-opt and transform his message into something that served their interests rather than challenged them.

The point isn't to worship Jesus, but to follow his example and teachings. The religion OF Jesus isn't about believing things about him—it's about doing what he did. It's about loving radically and inclusively, standing with the oppressed, challenging injustice, creating beloved community, working for transformation, choosing love over fear, and living with courage and hope.

The religion OF Jesus doesn't require us to believe Jesus was divine (though you can if you want to). It doesn't demand we accept medieval theories about blood sacrifice and atonement. It doesn't ask us to check our brains at the door or ignore the historical context of the Bible.

The religion of Jesus is much harder

What it does require is much harder—that we love. That we love God, love our neighbors, love ourselves, and even love our enemies. That we work to create what Jesus called the Kingdom of God—what Dr. King later called the Beloved Community—here and now.

This is the faith that inspired the civil rights movement, liberation theology, and countless other movements for justice and transformation. This is the Christianity we need today—not the version that props up power and privilege, but the revolutionary message of love and justice that Jesus actually taught and lived.

The question isn't "Do you believe in Jesus?" but "Will you follow Jesus?" Will you commit to the hard work of love? Will you stand with the oppressed? Will you challenge injustice? Will you help create beloved community?

That's what Jesus did. That's what he taught others to do. That's the religion OF Jesus. Everything else is just religion ABOUT Jesus.

For those millions turning away from Christianity, we say: we understand. What you're rejecting isn't the religion of Jesus. It's the religion about Jesus that betrayed his message. Perhaps it's time to rediscover what Jesus actually taught and lived — not through the lens of empire and power, but through his own words and actions as a poor, Palestinian Jew who showed us how to love radically in the face of oppression.

- Howard Thurman (1899-1981) was one of the most influential religious thinkers of the 20th century. A mystic, philosopher, and activist, he served as dean of Rankin Chapel at Howard University and later became the first Black dean at a predominantly white university when he led Marsh Chapel at Boston University. His 1949 book, Jesus and the Disinherited (Nashville: Abingdon Press), where his idea of the religion ‘of Jesus’ vs. the religion ‘about Jesus’ was first published, deeply influenced Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement.

- It’s worth pointing out here that the predominant notion of Jesus’s saving (or atoning) work in western Christianity today is only about 1,000 years old. The New Testament, while asserting that Jesus "saves," is much less clear on how and why. Here’s a brief look I wrote at five views on the Atonement of Christ.

- James Cone (1938-2018), the father of Black liberation theology, was a professor of theology at Union Theological Seminary in New York City. In works like God of the Oppressed (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1975), he argued that Jesus's message of liberation for the oppressed was corrupted when Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire in 380 CE, transforming from a religion of the oppressed into a tool of the oppressors.

- Delores S. Williams (1937-2022) was a pioneering womanist theologian and also a professor at Union Theological Seminary. In Sisters in the Wilderness (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1993, 164-165), she argues that Jesus came not to die but to show us how to live through his ministerial vision of transforming relationships between body, mind, and spirit. For Williams, there is "nothing divine in the blood of the cross"; redemption comes through following Jesus's way of life, not his death.

- The Greatest Commandment appears in all three Synoptic Gospels (Mk 12:28-34, Mt 22:34-40, Lk 10:25-28), which scholars consider our earliest and most historically reliable sources for Jesus's teachings. The Gospel of John, written decades later around 90-100 CE, reflects a more developed theological understanding of Jesus as divine and emphasizes belief in Jesus's divinity as central to salvation (see Jn 3:16, 14:6). However, most scholars agree John's Gospel represents later Christian theological development rather than Jesus's own teachings. For more on this distinction between the historical Jesus and later Christian theology, see Marcus Borg, Jesus: Uncovering the Life, Teachings, and Relevance of a Religious Revolutionary (HarperOne, 2006).

* * * * *