An essay by Ian Bruce 2000, in answer to the following question:

‘Does Foucault’s Madness and Civilization give us a new conception of madness, or does it only give us an historical account of how madness has been evaluated and treated in different eras? ’

Topics

Table of Contents

Introduction and Overview

Part 1: A Hermeneutic Conundrum

Part 2: An Artistic Solution

Conclusion

Bibliography

Introduction and Overview

This question raises some fundamental issues in the fields of language and history that are central to the endeavour that Foucault undertook with Madness and Civilization.

Firstly, the use of a word such as "madness" necessarily invokes a concept that is current at the time of writing. Any attempt at writing a history of madness must use the current word when referring to the concept "madness" as used in previous eras. This results in a fundamental contamination of the concept "madness" as held in previous eras by the concept contemporaneous with the time of writing.

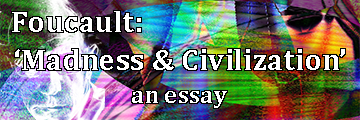

Secondly, a major observation that Foucault illustrates and develops in Madness and Civilization is that since the Classical Age (17th-18th centuries) "reason" (or the popular notion of common sense and logical appraisal) has been defined by a process of exclusion, confinement and silencing of madness along with other manifestations of "unreason" (Foucault 1988, p.107). This process has seen "madness" reduced to nothing (Foucault 1988, p.107) and the resources of history and scientific investigation, the language of discourse, effectively commandeered by "reason", such that any historical account of madness must be rendered using the tools that have been fashioned out of the silencing and relegating to oblivion of madness. (Derrida 1978, pp.34-35)

The foregoing problems and Foucault’s solution to them are considered in Part 1 of this essay. Foucault realises that a history of madness would be impossible to write. He thus aims to write an archaeology of the silence of madness (Foucault 1988, p.x). The conclusion of this section is that Foucault does not give us a new conception of madness, but provides an archive of archaeological material and observations from which we can construct for ourselves, a new conception of madness.

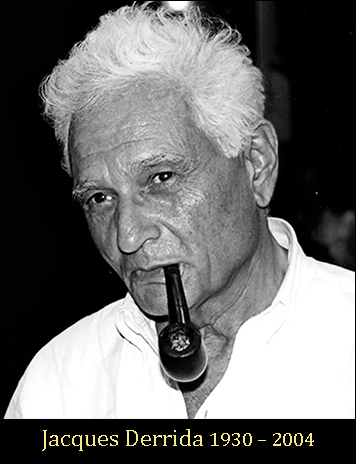

Part 2, looks at some of the techniques Foucault uses to achieve his aims. It considers Madness and Civilization as a work of literature. The notion that it gives an historical account of the evaluation and treatment of madness, is reviewed in the light of Foucault’s undisguised subjectivity in both selection and interpretation of material. The notion of "a conception of madness" is re-examined and found to be indirectly expressed through a careful construction of words and images, in a multi-level, multi-stranded artistic statement.

Part 1: A Hermeneutic Conundrum

The term hermeneutics is essentially an epistemological term that can refer to a range of human investigations. However, two essential features of the term are the notions that to understand the meaning of a part (a text, a word, an action, an historical event) requires the understanding of the whole to which it belongs and vice versa, and that to correctly interpret a text, the reader must imaginatively reconstruct the environment in which the text came into being (Mauntner, 1999, p.247). Foucault’s inquiry in Madness and Civilization exhibits a strong awareness of hermeneutic concerns, exemplified by his attempt to construct "archaeological" archives of material drawn from diverse fields: painting, literature, historical record, scientific documents. However, the hermeneutic problem is given a further dimension by Foucault’s acceptance of the basic propositions of Hegelian logic.

Hegel postulated that any determinate being, for example, a physical object, or a concept of a quality possessed by objects, not only possesses the specific qualities by which it is customarily defined, but also the negative qualities which it is thought customarily not to possess (Hartnack 1998, p.16). The identity conditions of the ‘something’ and the ‘something else’ are interdefined (Hartnack 1998, p. 22). The ‘something’ and the ‘something else’ actually have the same referent but a different mode of presentation (to use Gottlob Frege’s terminology) (Hartnack 1998, Introduction). One of the main discoveries that Foucault uncovers and develops is, that since the Classical Age or Age of Reason (17th-18th centuries), the accepted notion of "reason" has been defined by the exclusion of the negative qualities of "unreason". "Unreason", is a quality that Foucault finds has been attributed to a changing field of objects, people, and events through the various eras which he researches, but which, since the Classical Age has included the insane. The hermeneutic difficulty arises with the realisation that the language of inquiry, scientific investigation, the notion of histories and the descriptive power of the written word, is presumed to be the precinct of "reason", so that no description of madness or indeed unreason is possible. "The annexation of the totality of language ... by psychiatric reason" (Derrida 1978, pp.34) in the modern age, has ended all dialogue between madness and reason. Only the silence of madness can be witnessed.

If, to this "Hermeneutic Conundrum" is added the problem mentioned in the introduction, whereby a term such as "madness" necessarily invokes a modern meaning, and cannot be used to effectively refer to the concept "madness" as used in previous ages, we see that Foucault’s undertaking is vast and complex. Foucault thus expressly states that his aim is to construct an archaeology, not a history:

"I have not tried to write the history of that language [the language of psychiatry] but, rather, the archaeology of that silence [the silence of madness]." (Foucault 1988, p.x)

If by history, one meant the notion of a description or recounting of a past reality in the words of a current document, then an archaeology, in contrast, is merely the unearthing of some of the artefacts that have been left behind from that past reality. A history must necessarily make claims of describing the totality of the past reality, whilst the archaeologist, who may merely excavate one square metre of a midden heap from a city that covered hundreds of acres, makes no such claim. The archaeologist aspires, by the exactitude of his excavation and the careful preservation of the minute traces of meaning that each relic possesses, to construct an archive of relics which can be used by philosophers and historians to construct histories and descriptions of the physical, social and metaphysical reality that did exist.

Derrida, in his essay Cogito and the History of Madness (Derrida 1978), suggested that an archaeology was in fact a logic, and thus, that an archaeology of the silence of madness was in reality a history of madness (Derrida 1978, p.35). I feel however, that Derrida projects onto Foucault’s work the notion that it must be a scientific document, an expression of modern reason, merely from it being read by modern day thinkers and available for criticism by essays such as his. From my reading of the English translation of the work, I gained firstly the impression that it is a work of literature, not scientific discourse. The terms "madness", "reason" and "unreason" are used in a subtle and shifting way by Foucault, to avoid the hermeneutic trap of historicising in modern language. Foucault constructs archaeological archives for the various ages, and is careful to use the term "madness" as it was used by authors of the various periods. Of course, he also uses the terms on a different level in the extemporising narrative which binds the various archives together into the unity of the book. This usage is literary, and definitions are deliberately not supplied. These words are empty shells, or labels, to be filled out by the reader from the experience of examining the archival material.

Part 2: An Artistic Solution

Foucault states that he aims to construct an archaeology of the silence of madness because a history is impossible, due to the fact that the language of history is the language of the reason that has defined itself by the silencing of madness. However, I consider that he uses the notion of an archaeology as opposed to a history, as a structural ploy, aimed at giving his work the validity of a scientific paper without the restrictions of analysis that an historical-scientific paper would entail. I have no doubt that Foucault intended that his readers would derive a concept of "madness" from his work, but the concept of "madness-in-itself" as stated previously, would be something that the readers could construct from the archaeological archives he provides.

There is indeed a history of madness in the book, but it is of "that ‘other form of madness’ that allows men ‘not to be mad,’ that is, in relation to reason." (Derrida 1978, p.33) Foucault uses the word "madness" in several different ways throughout the book. Firstly, the madness that is considered to be a divine intervention in the middle ages, a folly in the Renaissance, an animal depravity or moral sin in the Classical Age and ultimately a disease in the modern era. Secondly, madness as one form of "unreason" in the Classical age, which becomes linked to outstanding examples of unreason, that are the inspirational utterances of geniuses like Nietzsche. Thirdly, as reason itself.

Foucault builds a picture of reason as not just a "logic" that fails to recognise its own shortcomings, but as a complex construction of the dominant social order and its mechanisms of power and suppression. Thus, the madness that is the "other" of any current reason, includes insights into the limitations, inadequacies and blatant domination of that reason. Ever since the Classical Age, when logic and empirical method set out to solve all mysteries and explain, in a logically consistent system, all of reality, more and more genuine aspects of human experience have been consigned to the realm of "unreason". It is this process, the ultimate insanity of the Magna Scientia used as a tool of suppression, that Foucault chronicles. The other madness, madness-in-itself, the genius of madness, Foucault carefully avoids defining or describing.

What Foucault undertook was a monumental task, and is one which would indeed be impossible in any scientific treatise. To achieve it, Foucault employs the devices of literature. For to achieve his aim would be a transgressive act, and as he came to declare later in his life, such a transgressive discourse is now only possible in literature.

Foucault draws his subject matter from diverse fields: his own musings on the significance of imagery in paintings from the medieval, Renaissance and Classical eras; scientific or medical writings; works of literature; historical events with associated bureaucratic records of a statistical or reporting nature. This in itself is a transgressive act in a document created under the auspices of modern day reason, because one of the hallmarks of reason is the separation of understandings of reality into discrete compartments, or academic disciplines, for example, history, archaeology, psychology, art, literature, scientific discourse. The fact that Foucault draws on these diverse sources when gathering the "artefacts" for his archives, and meanders through small selections of the available material, is a denial of the absolute power of reason to contain and silence the other of reason. For scientific discourse cannot appear to meander: reason demands that it is a totality, not merely one view of a totality.

The juxtaposition of material from diverse sources is also an attempt to locate the potentiality of conceptualising "madness", "unreason" and indeed "reason" in a structuralistic recreation of the environment of different eras. Thus Foucault attempts to transcend the hermeneutic problem of the contamination of concepts by present day historicising.

Conclusion

The question "does Madness and Civilization only give us an historical account of how madness has been evaluated and treated in different eras?" implies that "madness" is a constant that has carried through various historical eras. To accept this is to deny a central proposition of the work: that "madness" takes on a different sense and referent when the word is used in the context of the different archives which Foucault has constructed. After reading the book, one is left, not with a constant notion of "madness" but multi-dimensional mental spaces, within which the term, when uttered, evokes different meanings.

If you consider the saying: "In the kingdom of the blind, the one-eyed man is king;" and substitute for "blindness", the declared totality of reason, or as Foucault says: "the vain images of blind idiocy", (Foucault 1999, p.23), and for "one-eyed vision", the madness that exposes the limitations of reason, there is no era as surveyed by Foucault, in which the one-eyed man would be king. In medieval times, the one-eyed man, the madman, was thought to be touched by God, making him a a seer or sage. In the Renaissance, he was seen to be a fool: the victim of folly. In the Classical Age, the madman was a degenerate sinner, displaying the extremities of animalistic depravity that needed to be exhibited as a warning against transgression. In the nineteenth century, he was considered to be suffering from a strange disease. And in the modern age, his seeing-eye is considered to be a cancer that must be surgically removed or chemically suppressed.

Such is the power of Foucault’s work, that he is able to transcend historicising reason and the notion that concepts can exist in a pure form, isolated from the power structures of the era in which they are located. Instead of giving us a concept, he demonstrates the continuing process of concept formation: both the absolute identity of reason with unreason, and the perpetual struggle of reason to excise and silence its other.

Bibliography

Derrida, Jacques, 1978,‘Cogito and the History of Madness’, in 'Writing and Difference', translated by Alan Bass, Routledge & Kegan Paul.

p.33 ... for Foucault's enterprise is too rich, branches out in too many directions to be preceded by a method or even by a philosophy, in the traditional sense of the word. And if it is true, as Foucault says, as he admits by citing Pascal, that one cannot speak of madness except in relation to that "other form of madness" that allows men "not to he mad," that is, except in relation to reason, it will perhaps be possible not add anything whatsoever to what Foucault has said, but perhaps only to repeat once more, on the site of this division between reason and madness of which Foucault speaks so well, the meaning, a meaning of the Cogito or (plural) Cogitos (for the Cogito of the Cartesian variety is neither the first nor the last form of Cogito); and also to determine that what is in question here is an experience which, at its furthest reaches, is perhaps no less adventurous, perilous, nocturnal, and pathetic than the experience of madness, and is, I believe, much less adverse to and accusatory of madness, that is, accusative and objectifying of it, than Foucault seems to think...

In writing a history of madness, Foucault has attempted—and this is the greatest merit, but also the very infeasibility of his book—to write a history of madness itself. Itself. Of madness itself. That is, by letting madness speak for itself. Foucault wanted madness to be the subject of his book in every sense of the word: its theme and its first-person narrator, its author, madness speaking about itself. Fouctault wanted to write a history of madness itself, that is madness speaking on the basis of its own experience and under its own authority, and not a history of madness described from within the language of reason, the language of psychiatry on madness—the agonistic and rhetorical dimensions of the proposition on overlapping here—on madness already crushed beneath psychiatry, dominated, beaten to the ground, interned, that is to say, madness made into an object and exiled as the other of language and a historical meaning which have been confused with logos itself. "A history not of psychiatry," Foucault says, "but of madness itself, in its most vibrant state, before being captured by knowledge." ...

p.34 Sometimes Foucault globally rejects the language of reason, which itself is the language of order (that is to say, simultaneously the language of the system of objectivity, of the universal rationanty of which psychiatry wishes to the expression, and the language of the body politic—the right to citizenship in the philosopher's city overlapping here with the right to citizenship anywhere, the philosophical realm functioning, within the unity of a certain structure, as the metaphor or the metaphysics of the political realm). At these moments he writes sentences of this type (he has just evoked the broken dialogue between reason and madness at the end of the eighteenth century, a break that was finalized by the annexation of the totality of language—and of the right to language—by psychiatric reason as the delegate of societal and governmental reason; madness has been stifled): "The language psychiatry, which is a monologue of reason on madness, could be established only on the basis of such a silence. I have not tried to write the history of that language but, rather, the archaeology of that silence." And throughout the book runs the theme linking madness to silence, to "words without language" or "without the voice of a subject," "obstinate murmur of a language that speaks by itself, without speaker or interlocutor, piled

p.35 up upon itself, strangulated, collapsing before reaching the stage of formulation, quietly returning to the silence from which it never departed. The calcinated root of meaning." The history of madness itself is therefore the archaeology of a silence.

But, first of all, is there a history of silence? Further, is not an archaeology, even of silence, a logic, that is, an organized language, a project, an order, a sentence, a syntax, a work? Would not the archaeology of silence be the most efficacious and subtle restoration, the repetition, in the most irreducibly ambiguous meaning of the word, of the act perpetrated against madness,—and be so at the very moment when this act is denounced? Without taking into account that all the signs which allegedly serve as indices of the origin of this silence and of this stilled speech, and as indices of everything that has made madness an interrupted and forbidden, that is, arrested, discourse—all these signs and documents are borrowed, without exception, from the juridical province of interdiction... Total disengagement from the totality of the historical language responsible for the exile of madness, liberation from this language in order to write the archaeology of silence, would be possible in only two ways. Back

p.36 Either do not mention a certain silence (a certain silence which, again, can be determined only within a language and an order that will preserve this silence from contamination by any given muteness), or follow the madman down the road of his exile. The misfortune of the mad, the interminable misfortune of their silence, is that their best spokesmen are those who betray them best; which is to say that when one attempts to convey their silence itself, one has already passed over to the side of the enemy, the side of order, even if one frghta against order from within it, putting its origin into question. There is no Trojan horse unconquerable by Reason (in general). The unsurpassable, unique, and imperial grandeur of the order of reason, that which makes it not just another actual order or structure (a determined historical structure, one structure among other possible ones), is that one cannot speak out against it except by being for it, that one can protest it only from within it; and within its domain, Reason leaves us only the recourse to strategems and strategies. The revolution against reason, in the historical form of classical reason (but the latter is only a determined example of Reason in general. And because of this oneness of Reason the expression "history of reason" is difficult to conceptualize, as is also, consequently, a "history of madness"). the revolution against reason can be made only within it, in accordance with a Hegelian law to which I myself was very sensitive in Foucault's book, despite the absence of any precise reference to Hegel. Since the revolution against reason, from the moment it is articulated, can operate only within reason, it always has the limited scope of what is called, precisely in the language of a department of internal affairs, a disturbance. A history, that is, an archaeology against reason coubtless cannot be written, for, despite all appearances to the contrary, the concept of history has always been a rational one. It is the meaning of "history" ro archia that should have been questioned first, perhaps. A writing that exceeds, by questioning them, the values "origin," "reason" and "history" could not be contained within the metaphysical closure of an archaeology.

Foucault, Michel, 1988, Madness and Civilization: a history of insanity in the Age of Reason, (1961), abridged by the author and translated from the French by Richard Howard, Vintage Books, 1988.

p.ix

PREFACE

PASCAL: "Men are so necessarily mad, that not to be mad would amount to another form of madness"." And Dostoievsky, in his DIARY OF A WRITER: "It is not by confining one's neighbor that one is convinced of one's own sanity."

We have yet to write the history of that other form of madness, by which men, in an act of sovereign reason, confine their neighbors, and communicate and recognize each other through the merciless language of non-madness; to define the moment of this conspiracy before it was permanently established in the realm of truth, before it was revived by the lyricism of protest. We must try to return, in history, to that zero point in the course of madness at which madness is an undifferentiated experience, a not yet divided experience of division itself. We must describe, from the start of its trajectory, that "other form" which relegates Reason and Madness to one side or the other of its action as things henceforth external, deaf to all exchange, and as though dead to one another ...

p. x In the serene world of mental illness, modern man no longer communicates with the madman: on one hand, the man of reason delegates the physician to madness, thereby authorizing a relation only through the abstract universality of disease; on the other, the man of madness communicates with society only by the intermediary of an equally abstract reason which is order, physical and moral constraint, the anonymous pressure of the group, the requirements of conformity. As for a common language, there is no such thing; or rather, there is no such thing any longer; the constitution of madness as a mental illness, at the end of the eighteenth century, affords the evidence of a broken dialogue, posits the separation as already effected, and thrusts into oblivion all those stammered, imperfect words without fixed syntax in which the exchange between madness and reason was made. The language of psychiatry,

p. xi which is a monologue of reason about madness, has been established only on the basis of such a silence. I have not tried to 'Write the history of that language, but rather the archaeology of that silence. Back

p.23 On all sides, madness fascinates man. The fantastic images it generates are not fleeting appearances that quickly disappear from the surface of things. By a strange paradox, what is born from the strangest delirium was already hidden, like a secret, like an inaccessible truth, in the bowels of the earth. When man deploys the arbitrary nature of his madness, he confronts the dark necessity of the world; the animal that haunts his nightmares and his nights of privation is his own nature, which will lay bare hell's pitiless truth; the vain images of blind idiocy-such are the world's Magna Scientia; and already, in this disorder, in this mad universe, is prefigured what will be the cruelty of the finale. In such images—and this is doubtless what gives them their weight, what imposes such great coherence on their Back

p.24 fantasy—the Renaissance has expressed what it apprehended of the threats and secrets of the world. Back

p.107 Joining vision and blindness, image and judgment, hallucination and language, sleep and waking, day and night, madness is ultimately nothing, for it unites in them all that is negative. But the paradox of this nothing is to manifest itself, to explode in signs, in words, in gestures. Inextricable unity of order and disorder, of the reasonable being of things and this nothingness of madness! For madness, if it is nothing, can manifest itself only by departing from itself, by assuming an appearance in the order of reason and thus becoming the contrary of itself. Back

Foucault, Michel, ‘My Body, This Paper, This Fire,’ translated by Geoff Bennington, in Oxford Literary Review, Vol. 4, 1979: 9-28. Back

Hartnack, Justus, An Introduction to Hegel’s Logic, translated from the Danish by Lars Aagaard-Mogensen, Hacket Publishing Company Inc. Indianapolis, 1998. Back

Mautner, Thomas. The Penguin Dictionary of Philosophy, p.247, Penguin Books, London, 1997.

hermeneutics (Gr. hermeneuein to translate, interpret, make intelligible) n. sing. 1 interpretation. 2 inquiry into, or theory of, the nature or methods of interpretation.

There has been reflection on the art of interpreting texts since ancient times, but the word ‘hermeneutics’ was first used by J. C. Dannhauer in the mid-seventeenth century. He noted that texts for which a theory of interpretation was needed fell into three classes: Holy Scripture, legal texts (statutes, precedents, treaties, etc.), and the literature of classical antiquity.

One important problem for traditional hermeneutics was that it had two radically different aims in its main areas: theology and jurisprudence. One aim was to provide a correct interpretation, the other to establish an authoritative statement of dogma or of law. It can at times be difficult to satisfy both requirements, and this is why it has been said that hermeneutics is the art of finding something in a text that is not there. Back