When you hear a list of nouns — say: ‘birds’; ‘reptiles’; ‘fish’; — your mind automatically searches for a common factor — a commonality — possessed by each in the group. In this case you might think ‘animals’.

The terms ‘Philosophy’, ‘Religion’ & ‘Spirituality’ are often reeled off as if they were names for subjects or areas of thought that could be grouped under one category. But when you look at the terms closely this is not the case.

These three terms are as similar to one another as a recipe is to a cake, is to the act of eating cake.

Philosophy

The word ‘Philosophy’, comes from the Greek ‘phileo’ (φιλεω), ‘love’. and ‘sophia’ (σοφια), ‘wisdom’. In the time of Plato (5th-4th century BC) philosophy referred to all learning, including ‘natural philosophy’, which today — since the 17th Century — we call the sciences. (Webster's dictionary has a good description of traditional categories of ‘philosophy’. (link)

Philosophy is essentially descriptions in words of mental schema for ‘understanding’ things. For example, the philosophy of a religion consists of descriptions in words of the beliefs (including cosmology) and parctices of the religion in question.

Religion

You often hear the term ‘religion’ bandied about, as if it is a basic word in the English vocabulary, like ‘stone’ or ‘tree’. But when you try to find a definition of the term, you encounter a mass of shifting relativities.

In the introduction to the 2021 printing of the Australian Constitution, the Government Solicitor declares: ‘a right exists to exercise any religion’. (link) But the only mention of the term ‘religion’ in the constitution itself, is in Section 116:

‘The Commonwealth shall not make any law for establishing any religion, or for imposing any religious observance, or for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion, and no religious test shall be required as a qualification for any office or public trust under the Commonwealth.’ (link)

And nowhere in the Constitution, nor in the introduction, is there a definition of the term ‘religion’.

The Australian Constitution was drawn up in the 1890s, and Section 116 is written in a context that stretches back to Henry VIII's break from the church of Rome (in the 16th century), and the Catholic-Protestant tensions that erupted in the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688, followed by the Act of Settlement of 1701, which secured the protestant succession to the UK throne. (link) The authors of the constitution were not thinking of Mormons, Buddhists, or even Islamists — it was just the Catholic-Protestant divide.

In Australian case law, we can find some defining criteria for what can be called ‘a religion’ (link):

A religion is essentially an inert structure: a combination of ideas, images, beliefs & practices (using my image of a cake made from the recipe of its philosophy).

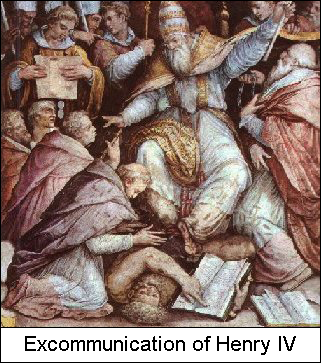

It is important to note that when someone says they 'follow' a particular religion, there is no automatic association with spiritual striving and development. In many cases, a religion is 'followed' because the person has been brought up in a family that 'followed' the religion. The beliefs and practices are accepted by the person, by custom or tradition, but often also, under threat of ostracism or excommunication (or similar), and no verification of actual belief is undertaken other than rote learning and the following of routine practices. Whether the resources of the religion are used by the individual to pursue 'spirituality' is an individual matter — not a necessary consequence of their 'following' the religion.

Spirituality

'Spirituality' derives from 'spirit' — incorporeal being, as opposed to matter. (Webster's dictionary link).

In common usage, a person who is 'into spirituality', is concerned to develop their perceptions and facility with non-physical planes of being — often associated with an endeavour to become a 'better' person, and overcome the neuroses and distortions of perception they have accumulated through their life.

There are a host of conceptual structures used to explicate an individual's spiritual endeavours: planes of consciousness; god consciousness; etc.. And there are many 'schools' of spiritual development which veer towards our definition of 'established religion'. However, an individual who seeks spiritual awareness and development essentially follows their own path, though they may use the structure and resources of an established religion or spiritual school. In our 'cake' metaphor, the person so engaged, is eating cake.

Effects of confused definitions

The association of genuine endeavour to attain spiritual awareness and development with established religions is spurious. How can a religion that threatens followers with ex-communication, hell fire, or (in some cases), death, if they leave the fold, be associated with spiritual development? We are looking at an organisation exercising monopolistic tyranny — something quite evil.

Once a religion is established — with followers, priests (officials), written dogma, property, influence — it is, for all intents and purposes, an economic entity — a business — and via the power of the sheer numbers of adherents, a powerful political lobby.

You often hear freedom of religion glossed as: believe and do as you like as long as you don't break any laws or inhibit the rights of others. However, established religions routinely contravene basic Australian laws.

For example:

There was much discussion in Australia in 2022 about allowing established religions to discriminate, based on their beliefs (i.e. contravene existing Australian laws). However, the entire discussion is based on a vague and incoherent understanding of religion and spirituality. The discussion should be about personal freedoms, including the freedom to pursue spirituality. Established religions should be treated as the commercial enterprises they actually are, and be subject to the established laws of the state.

Followers of a religion should not be treated any differently from shareholders or employees of a particular company. What we should be protecting is the freedom of the individual to seek spiritual awareness and advancement in whatever way they choose, provided they don't break fundamental laws or impinge on the freedoms of others. And any established religion that practices such coercive and extortionist practices as excommunication, shunning or other threats of harm, financial demands, etc., (link) should be dealt with under the criminal and trade practices laws, as appropriate.

Conclusion.

The terms ‘Philosophy’, ‘Religion’ & ‘Spirituality’ look deceptively similar when reeled off in a list. However, I think the metaphor of ‘recipe’, ‘cake’, and ‘eating cake’, is a useful tool to keep in mind when any issues — directly or indirectly related — are being discussed.

* * * * *