This is a transcript of a 14 minute video put out by the ABC VideoLab April 2023. (video link)

Introduction: [series of a few words short clips]

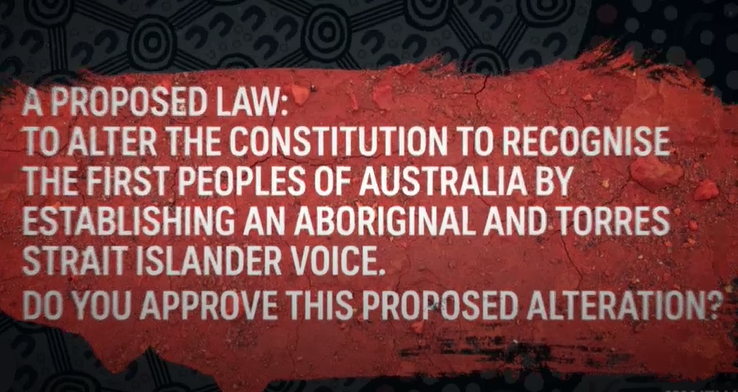

Dana Morse ABC political reporter: Here's a question that every Australian of voting age will have to answer this year:

A proposed law to alter the contsitution to recognise the first peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander voice. Do you approve this alteration?

It's a big question but your answer will be as simple as 'yes' or 'no'.

It's a question that for many poses a few more questions like:

What is an indigenous voice?

Why is it up to us to decide whether or not it exists?

[short clip]

Anthony Albanese clip: 'All of us will have an equal say. All of us can own an equal share of what I believe will be an inspiring and unifying Australian moment.'

[end of short clip]While there's a lot of talk about the voice things aren't necessarily getting any clearer.

[series of short clips]

Fox News clip: 'Support for an Indigenous voice to parliament has stalled.'

Patrick Dodson clip: 'I mean, all people are asking for is to have a say.'

Jacinta Price clip: 'We don't need a voice we need ears.'

Today Show clip: 'The confusion comes into it when we're not sure what the powers will be.'

Mark Drefus clip: 'The power that's given to the voice is to make representations.'

Peter Dutton clip: 'The prime minister has gone dow the path where he sees political opportunity and an attempt to wedge. And I don't think that's in our country's best interests.'

Linda Burney clip: 'This is a once in a generation chance.' [end of short clips]

So before you vote it's a good idea to know aht's at stake.

Here's everything that you need to know about the voice.

Let's start with the basics.

The plan is to put the voice in the Constitution—the document that outlines how Australia is governed.

To do anything to the Constitution there has to be a national vote—the referendum.

As a country we don't change the Constitution often. In fact we've only tried 44 times in our history—on everything from the railway disputes, to local government, to the length of parliamentary terms.

[short clip]

Professor Anne Twomey clip:

So change the Constitution, they're stuck with that for a long time. It's entrenched there and it's very hard to remove. And that makes people very wary of voting for change.

[end of short clip]

2023 will be the first time in nearly thirty years that we've had a referendum. Your vote will decide whether there should be a group of Indigenous Australians who advise the government on the issues that effect them and their communities.

But why do people want a voice in the first place?

Since Federation, most governments have struggled to make decisions that improve the lives of Indigenous people. Take the 'White Australia policy' or the 'Stolen Generation'. They were actually policies that made the lives of Indigenous people much harder.

Combine that with the issues caused by colonisation, and a lot of Indigenous people are worse off than the broader population in terms of health, wealth and education.

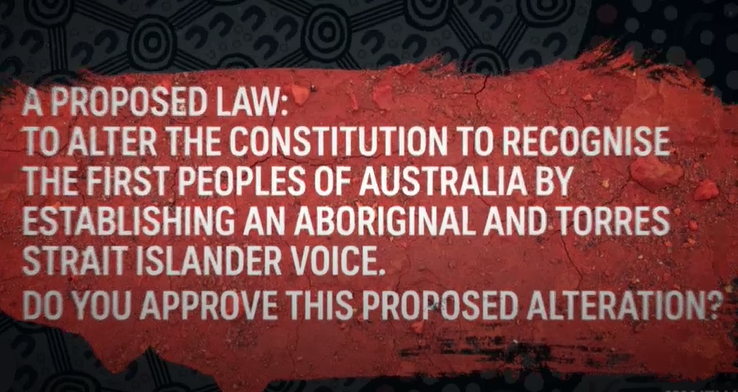

Closing that gap has been the aim of a lot of different governments. But nothing has made a huge difference so far. And as of last year, the gap is mostly getting wider. Of all the areas being measured, just a few are on track. COme are actually going backwards.

ON TRACK

Employment

Preschool enrolment

Youth detention

WORSENING

Adults in prison

Suicide rate

Child-removal rates

And Indigenous people are still living much shorter lives.

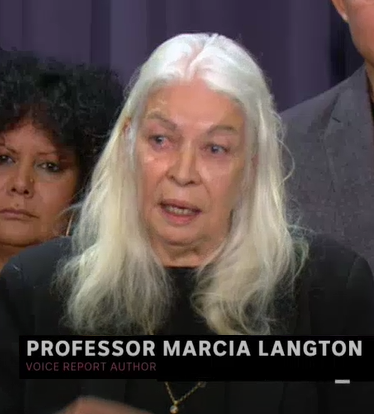

That's where the voice comes in. Getting Indigenous people to have a say over what happens to them—sometimes called self-determination—is seen as one of the best ways to close the gap.

[short clip]

Marcia Langton clip: And we know, from the evidence, that what improves lives is when they get a say. And that's what this is about.

[End of short clip]

Ideas for something like a voice have been around for a long time. But this version took shape a few years ago.

Let me take you back to 2017 to the Uluru National Constitutional Convention.

Indigenous leaders from across the country gathered in the red centre to try and come up with a plan to improve the lives of their communities.

[short clip]

Aunty Pat Anderson: There has to be some really fundamental change in the relationship. Australia has to hear us for goodness sake.

[End of short clip]

After days of talks a concensus was reached on the Uluru statement. 400 words that outline what Indigenous people say needs to change. The statement asks for three things: Voice; Treaty; and Truth.

[short clip]

Malcolm Turnbull: It's very short on detail. But it is a very big idea.

[End of short clip]

Six years on, plenty of research and consultation has been done with communities, organisations and governments. And many believe the voice is the best compromise to deliver change for Indigenous peoples.

This is where it landed.

The Voice would be a group of Indigenous people who advise government on whether propored policies and laws would be good or bad for their communities.

And here comes the important bit. These are the three snetences that could be added to the Constitution in order to create the Voice:

"In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Voice.

The Torres Straight Islander Voice may make representaions to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander peoples.

The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Voice including its composition, functions, powers and procedures."

It seems straight forward and is what the Uluru statement is calling for. But nothing's that easy, and this is where the debate begins.

There are two statements amongst all that that have raised questions about the proposal. And that's 'make representations' and 'Executive Government of the Commonwealth'.

For some who are arguing the 'No' case that gives the Voice too much freedom to get involved with a whole wide range of issues.

If the referendum succeeds, the Voice will be enshrined in the Constitution. Basically meaning it can't be disbanded or gotten rid of down the track. Something that has happened to First Nations bodies in the past.

[short clip]

ABC news reader: It won't be officially abolished until July. But the Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Commission is already being stripped of its 70 million dollars worth of assets.

Marcia Langton: Well what has happened in most cases, a party will appeal to the voters, that it will get rid of this 'x, y, z' body because it's clear that it's not working. And that's happened, I think we've reckoned seven times in our history.

[End of short clip]

The nuts and bolts of the Voice will be laid out in legislation, but would have to pass the parliament. That means over time all those details could be changed. But the Voice would still exist in some form.

There are plenty of questions about who and how many people would be on the Voice. How they would get elected. What their responsibilities would be. And some people want answers on that before they vote on whether a voice should exist.

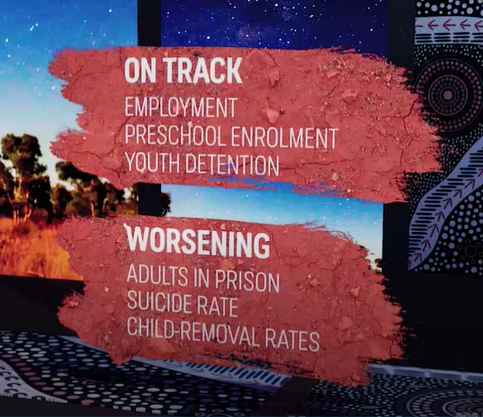

There are ideas about a lot of those things already. Most of them come from this report.

Professors Tom Calma and Marcia Langton wrote it in 2021, after speaking with thousands of people and organisations across the country.

So let's talk detail.

Their model for the Voice is twofold

First, there would be local and regional Voice groups. That would be designed and run by communities, in whatever way suits them best. The idea is to move away from organisations acting on behalf of communities, and empower them to speak for themselves.

Those local and regional groups would feed into a national Voice—24 different people covering 35 regions. Five of them would represent the remote communities and three would be from the Torres Straight. The local and regional groups would decide who gets to be on a national Voice.

Then the different Voice groups would work with each other at all different levels of government—from the federal parliament to the local council.

The expectation is that the Voice would be consulted early on in policy making when it affects Indigenous peoples. And the voice would road-test ideas and make suggestions on how they could be improved.

The Voice wouldn't have the power to stop policies and laws from going ahead. And any advice it gave could theoretically be ignored.

This isn't necessarily the model the government would evebtually put into law. But given how much consultation went into the report, it'll at least be a starting point for whatever ends up being put to the parliament.

So why won't the government tell us exactly what the Voice will be before the vote?

The thing is with the detail on the voice, even if the referendum succeeds, the parliament will still write the laws on it. That legislationwould still go through the parliament.

So things like how many people are on it, how much public funding it gets, could be debated and changed. Like any bill.

Secondly, a general rule of thumb for getting a referendum over the line, is keeping it simple.

Section 128 says the constitution can only be changed when a double majority is reached at a national vote. That means a majority of all voters as well as well as a majority of the states have to vote 'yes'. So to get it over the line the referendum would need the support of over eight and half million of the seventeen million enrolled voter and four out of the six states. Votes in the territories would go towards the national vote total.

Of 44 referendums held to try and change the constitution sionce 1901 only 8 have been successful. And the last successful vote was back in 1977. And that's why the government is resisting giving too much detail. It doesn't want the debate about what the Voice could be to drown out whether we should have one. And that's what happened to the republic.

[short clip]

Spokes woman on ABC news: 'The Australian people have had their say and they have said no.'

[End of short clip]

Experts petty much agree one of the reasons the republic proposal didn't pass was the debate stopped being about whether or not Australia should be a republic and turned into a debate about what kind of republic it should be.

[short clip]

Professor Anne Twomay: 'It's the sort of area where you need to keep all supporters together and not break off into factions, because once that happens it's more likely to fail, and it might well take another 20, 25, 30 years before you can get it back on the agenda again.'

[End of short clip]

This time around the government is trying to avoid those pitfalls. By balancing symbolic words with tangible actions. And keeping it to one simple question on the principle of a Voice whether there should be an indigenous group that advises government about policies, 'yes' or 'no'.

There's another part of this, and that's the truth telling and treaty part of the Uluru statement. It's called a makarata commission, and it's equally important but it's not what we'll be voting on at the referendum.

So where are we at now?

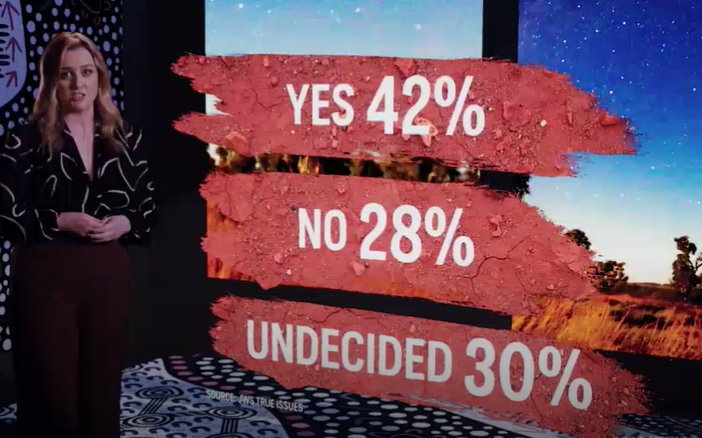

Usually for an issue to make it to a referendum, experts say around 90% of the community should be in favour, because over the course of a campaign, that number will drop, as more people find out about the issue and make their minds up.

Polls aren't perfect, but none have support for the Voice in the community ranking that high. At least a quarter of the population have already said that they'll vote no. Up to a third say they're undecided. Which means the 'yes' vote started the campaign with less than half of the population's support.

Even within the indigenous communities there are a range of views on the voice. And there are questions being raised over whether this is the right thing to do.

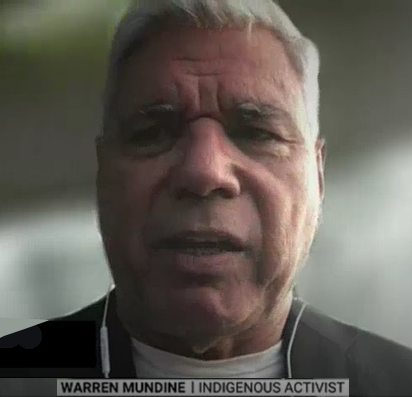

[End of short clip]

Lidia Thorpe: Do we wanna become an advisory body to the colonial system?

Warren Mundine: [We've] not fixed the economic issues, education and so on, that needs to be done.

Murrieguel Coe Craigie: We want our own black parliament. We want self-determination.

[short clip]

Many have lived through indigenous bodies being created and corrupted and abolished. And have lost faith in institutions.

There is also the fact that the Voice will be able to give advice only. For the parliament and governments don't have to take it onboard. That has some worried it'll just be symbolic and not deliver real change.

Some people want more action on truth telling and treaty, before the voice. And some want more practical policies tackling disadvantage to be rolled out.

Others want a different type of recognition, like seats in the senate reserved for Indigenous representatives where they could theoretically have more of a say.

And there are those who see the Constitution as a colonial document, and they don't want to be recognised in it.

In the broad population there are some who don't think Indigenous Australians should have a designated channel to the parliament.

But supporters say change has to happen. And this model is the best compromise to get First Nations people both constitutional recognition and a say on government policy

[short clip]

Professor Anne Twomay: 'The existence of a Voice ' for Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander people does not negate anyone else's ability to be heard and have their voices heard as well. It's not a zero sum game here.

[End of short clip]

So that's just about everything you need to know before you decide whether you vote 'yes' or 'no' to change the constitution. Everyone will get an equal say over what happens.

And whatever way the vote lands, it'll be a defining moment for the nation.

* * * * * * *