An article on medium.com, 11th January 2025, by Dylan Evans, describing the crimes against humanity being perpetrated by the USA government in their Guantanamo Bay facility. (article)

Guantanamo at 23

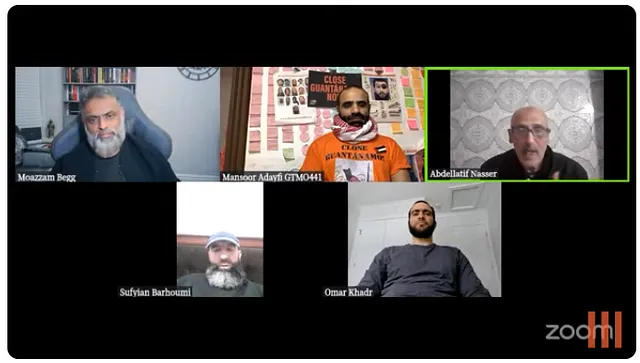

Former detainees from Guantanamo speak at an online event organised by CAGE.

Twenty three years ago today, on 11 January 2002, the first detainees were transported to Guantanamo Bay. This first group of twenty prisoners found themselves incarcerated at a brand new detention facility, specially built to house individuals captured during the US invasion of Afghanistan following the attacks by Al Qaeda on September 11, 2001.

These detainees were classified as “unlawful combatants” by the US government, a designation used to argue that they were not entitled to protections under the Geneva Conventions. This marked the beginning of what would become a highly controversial detention program, widely criticised for human rights abuses, indefinite detention without trial, and the use of torture. At its peak, Guantanamo Bay held nearly 800 detainees. Today, following the recent transfer of eleven Yemeni detainees to Oman, only fifteen remain.

The current detainee population includes individuals at various stages of legal proceedings:

Efforts to close the detention centre have been ongoing for years, and yet there is still no end in sight.

To mark this tragic anniversary, CAGE held a powerful online event featuring first-hand testimonies from some former detainees. The stories they told about their time in Guantanamo Bay were often harrowing, but also testified to their faith, resistance, and courage. The event was a powerful reminder that the fight to close Guantanamo and seek accountability is still ongoing.

What lingered most painfully in my mind, when the event was over, was the discussion of Abu Zubaydah, who has been called CAGE held "the forever prisoner" since the US authorities appear determined to keep Zubaybah in prison for the rest of his life, despite his total insignificance from a terrorism point of view. That is also the title of the documentary about Abu Zubaydah that Alex Gibney made in 2021.

A travesty of justice

Zubaydah’s ongoing detention is such an appalling travesty of justice that one would expect the details to be widely known. And yet, thanks to the US government pulling out all the stops to keep the story under wraps, few people know even the most basic facts. Here, then, is what everyone should know about the most famous prisoner at Gitmo.

Abū Zubaydah is a Palestinian citizen who was born in Saudi Arabia on 12 March, 1971. His birth name was Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn. Zubaydah was captured in Pakistan in March 2002 and has been in United States custody ever since, including four and a half years in the secret prison network of the CIA. He was transferred among black sites in various countries including a year in Poland, as part of a United States extraordinary rendition program. During his time in CIA custody, Zubaydah was subjected to extensive interrogation and torture; he was waterboarded 83 times and subjected to numerous other torture techniques, including forced nudity, sleep deprivation, confinement in small dark boxes, deprivation of solid food, stress positions, and physical assaults. Videotapes of some of Zubaydah’s interrogations are allegedly amongst those destroyed by the CIA in 2005. Zubaydah and ten other “high-value detainees” were transferred to Guantanamo in September 2006. He and other former CIA detainees are held in Camp 7, where conditions are the most isolating.

At his Combatant Status Review Tribunal in 2007, Zubaydah said he was told that the CIA now realized he was not significant: “They told me, ‘Sorry, we discover that you are not Number 3, not a partner, not even a fighter,’” said Zubaydah, speaking in broken English, according to a transcript of the Tribunal. The US government has not officially charged Zubaydah with any crimes. And yet the Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture reported that Zubaydah’s CIA interrogators wanted him to “remain in isolation and incommunicado for the remainder of his life.” Why?

Many different factors have contributed to the US authorities’ apparent determination to keep Abu Zubaydah detained indefinitely, even in the absence of charges or significant evidence of his involvement in terrorism. A combination of bureaucratic inertia, political concerns, legal ambiguities, and the long shadow of post-9/11 counterterrorism practices have combined to produce one of the worst miscarriages of justice in US history.

In sum, Zubaydah’s continued detention is not primarily about his alleged significance as a terrorist but rather about protecting institutional reputations, avoiding accountability, and maintaining control over the narratives surrounding post-9/11 counter terrorism efforts. His case exemplifies how individuals can become trapped in a system designed more to perpetuate itself than to achieve justice or security.

The moral bankruptcy of the United States

None of the reasons listed above for the continued detention of Abu Zubaydah meets even the most minimal ethical criteria or moral justification for imprisonment. In fact, most of them involve extreme and flagrant violations of fundamental moral rules and ethical norms. The continued detention of Abū Zubaydah without charges, coupled with the extensive use of torture and the systematic suppression of accountability, is an unambiguous moral failure. It constitutes a damning indictment of the systems and institutions that enabled, justified, and perpetuated such egregious violations of fundamental ethical principles.

At its core, Zubaydah’s case defies basic moral rules that underpin any just society, such as respect for human dignity, the presumption of innocence, and the prohibition of torture. The fact that he has been imprisoned for over two decades without charges or a fair trial renders his detention a grave injustice. Torturing someone, then admitting they were not the person you thought they were, yet continuing to imprison them, is a grotesque abdication of moral responsibility.

The destruction of evidence, the refusal to grant Zubaydah a fair hearing, and the persistent use of legal loopholes to avoid accountability all highlight a systemic evasion of justice. These actions suggest not only a lack of ethical governance but also a deep institutional rot where protecting power and reputation outweighs the imperative of righting profound wrongs.

The US often positions itself as a global champion of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law. Yet the treatment of detainees like Zubaydah starkly contradicts these ideals. It reveals a double standard: these principles are championed only when convenient, while actions like indefinite detention, extraordinary rendition, and torture betray those very values.

Zubaydah’s case is emblematic of the ways in which the “War on Terror” eroded international norms, such as the Geneva Conventions, the prohibition on torture, and the basic principles of habeas corpus. By flouting these norms, the US not only harmed Zubaydah and others like him but also weakened the global framework of accountability, setting dangerous precedents for other nations. The American “War on Terror” has also involved widespread violations of other ethical and legal norms, including indiscriminate drone strikes, extraordinary renditions, black sites, mass surveillance, and the dehumanization of entire populations. Abū Zubaydah’s case serves as a particularly stark example of the wholesale breakdown of an entire country’s moral compass.

The systemic dehumanization embodied in Zubaydah’s detention and torture reflects broader social failures. When a government violates human rights on such a scale, it sends a chilling message about the value of human life and dignity. These actions reverberate beyond Guantanamo, fostering cynicism, distrust, and alienation both domestically and internationally.

The fact that Zubaydah remains a prisoner implicates not just the military and the CIA but the broader political, judicial, and social systems that allowed this injustice to happen and still permit it to continue. Congress, courts, and successive administrations — both Republican and Democratic — have all played a role in perpetuating this injustice, whether through direct action, passive complicity, or failure to challenge the status quo. The United States of America itself stands condemned by this horrific abuse of power. There is not just something rotten in the US; the very foundations of its legitimacy are completely undermined.

To continue holding Zubaydah, not out of genuine security concerns but to preserve institutional pride and avoid accountability, is not just a failure of justice; it is a profound moral crime. It underscores the dangers of unchecked power and the corrosive effects of fear-driven policymaking on the very values that a society claims to uphold. Such an indictment demands not only acknowledgement but systemic reform, reparations for those wronged, and a reckoning with the past — none of which, sadly, seems forthcoming.

The “forever prisoner,” Abu Zubaydah

* * * * *

© Copyright 2025 Dylan Evans