The word 'épistémè' is not found in any major English dictionary. It is a word from ancient Greek meaning 'knowledge'.1*

The word was introduced into the vocabulary of modern philosophy by Michel Foucault in his 1966 work, 'Les Mots et Les Choses' (Words and Things).

He describes épistémè as:

‘In any given culture and at any given moment, there is always only one épistémè that defines the conditions of possibility of all knowledge, whether expressed in a theory or silently invested in a practice.’

Foucault's theories address the relationship between power and knowledge, and how they are used as a form of social control.

He debunks the notion that the modern sciences offer universal scientific truths about human nature. Rather he shows that these ‘truths’ are often merely expressions of certain ethical and political commitments a society has accrued as the outcome of contingent historical forces.

Foucault sees the 'épistémè' as setting 'the conditions of possibility of all knowledge'. But here, he is being the intellectual — the scientist — it all sounds clinical, an exercise in logic and scientific method. However, the methods of enforcement of the episteme, which he uncovered in his earlier work, 'Madness & Civilization' are ruthless.2*

He traces the history of society's treatment of madness (and people harbouring 'deviant thought'), through the ages. He groups people considered 'mad' and those who are considered 'deviants from the norm under the heading 'unreason', against society's forces of convention and conformity society's accepted reality, 'reason'.

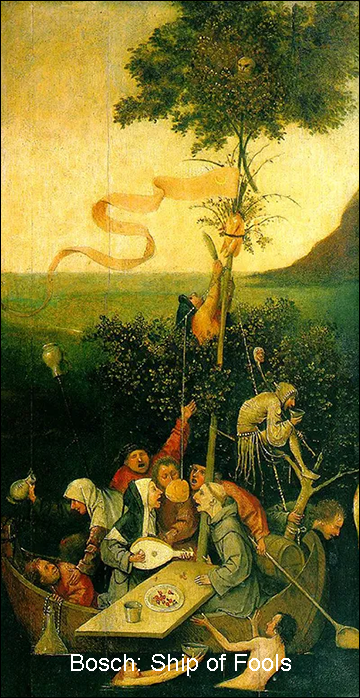

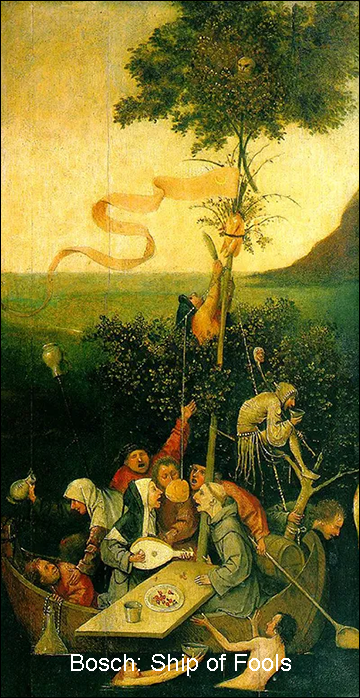

In the Renaissance the treatment of 'unreason' was exile.

In the 18th century, the Age of Reason, the treatment was confinement and condemnation as moral depravity.

In the 19th century, mockery & ridicule, was followed by medicalisation which lead to the modern age where the voice of unreason is finally silenced.1*

Part of the silencing mechanism is the userpation of the entire language, so that there are no words left that can express divergent views. A striking modern example is political correctness. there are nho words that people can use to express racial or cultural awareness. We are all being forced into the cancel-culture world where racial and cultural differences between people are blanked from consciousness.

In ‘The order of things’

The Renaissance

In the Renaissance the relation between words and things was understood to be primarily one of resemblance. Theory, principally, consisted in uncovering similarities, correspondences between things, between words and things, between words and words. He described a multiplicity of types of similitude, some being: convenience (the proximity or contiguity of things), emulation (resemblance at a distance), analogy (proximal or distant), sympathy (which can draw things together).

The Renaissance read marks in nature to discover similarities. Everything was like a written sign (Foucault speculated that that may have been due to the advent of printing at that time). Words and things were entwined: words were marks which resembled things; things bore marks which could be read like words. This supported a continuity between seeing and saying, which was to disappear in the Classical Age and reappear as a problematized relation in the Modern Age.

The change between the sixteenth century and the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was that in the latter the language began to be considered a case of representation and not of correspondence, introducing this way a discontinuity in the alleged, uncritical, and magical community between language and world. It was therefore introduced a critical distance between things and words, and their correspondence was maintained only in literature and art as a kind of compensation for the development of knowledge.The relation between word and thing in the Renaissance is a ternary relation i.e. a three term relation. There is (i) the mark; (ii) what it is the mark of; and (iii) the relation between the mark and what it is the mark of. This relation is resemblance. But because the relation of resemblance is a symmmetrical relation, where the mark is like what is marked and vice versa, the ternary relation between words and things ultimately reduces to the singular relation of resemblance.

The Classical Age (to the end of the sixteenth century)

The relation between word and thing in the Classical Age was that of representation, and ordering, identity and difference, as categorization and taxonomy.4* There is a radical separation of things into the binary relation of sign and signified. It is no longer the case that everything is seen to resemble everything else, nor that signs always resemble what they signify. Sometimes signs are seen to resemble what they signify (in the case of 'natural signs'), but at other times are seen to be quite unlike what they signify (in the case of arbitrary of conventional signs).

Rather than existing alongside signs on the same ontological and epistemological level, representational signs stand in place of the things they signify. The signified having been analysed in terms of identity and difference with other objects in the classifactory system (taxonomy). This parallels with the identifying of reason in the Classical Age by the exclusion of unreason. 'The madman and the poet are a surplus, produced and assimilated by modern culture as a result of the establishment of the new episteme based on Descartes’ gesture that rejects the complexity of the similarities of the world, introducing the simplicity of the order of thought as a fundamental measure.'

The Modern Age

Foucault observes Self-referentiality within a medium is a hallmark of modernity. However, he also observes it as an indication of a transitional phase between one epoch and another.

When Foucault talks about 'the conditions of possibility of all knowledge' he is being the intellectual, the scientist. And it all sounds clinical — an exercise in logic and scientific method. However, the methods of enforcement of the episteme, which he uncovered in 'Madness & Civilization' are clinical in their ruthlessness:

Exile — confinement —Moral condemnation — Mockery & Ridicule — Silencing.

These are the tools of ruthless suppression we associate with Fascist regimes. And yes! Foucault is saying that we live in such a society.

Look at this passage from ‘How the Mind Works’ by Steven Pinker, a distinguished cognitive psychologist:

p. 4 ‘In a well designed system, the components are black boxes that perform their functions as if by magic. That is no less true of the mind. The faculty with which we ponder the world has no ability to peer inside itself or our other faculties to see what makes them tick. That makes us the victims of an illusion: that our own psychology comes from some divine force or mysterious essence or almighty principle. In the Jewish legend of the Golem, a clay figure was animated when it was fed an inscription of the name of God. The archetype is echoed in many robot stories. The statue of Galatea was brought to life by Venus' answer to Pygmalion's prayers; Pinocchio was vivified by the Blue Fairy. Modern versions of the Golem archetype appear in some of the less fanciful stories of science. All of human psychology is said to be explained by a single, omnipotent cause: a large brain, culture, language, socialization, learning, complexity, self-organization, neural-network dynamics.’

The modern scientific episteme is one of physicalism. Belief in spiritual dimensions, let alone an omnipotent God, is generally labelled as a fantasy. Despite the fact that any philosopher will tell you that the existence of a divine, transcendent, God force, can neither be proved nor disproved. The modern scientific episteme takes the absence of proof of a divine presence as proof of its absence.

The process of allowing the possibility of a 'knowledge' — giving permission — 'silences' the 'unreason' of belief in a God. No dialogue is entered into. Pinker starts by labelling the perception (or belief) in a God principle as a fairy tale (an ad hominem logical fallacy).

In the next paragraph he does announce his intention 'to convince you that our minds are not animated by some godly vapor or single wonder principle'. But he has already prepared the ground by deriding (ad hominem) and ridiculing the notion (ad absurdum).

In ‘The order of things’, Foucault explores how man came to be an object of knowledge. He argues that all periods of history have possessed certain underlying (limiting) conditions that enable the production and reception of knowledge within that epoch — what was acceptable as scientific discourse — the conditions for the emergence of knowledge. He observes that these conditions of discourse change over time, from one period's épistémè to another.

Foucault also observed that the concept of 'madness' was never restricted to conditions we now think of as mental illness, but has always included the thoughts and lives of pwople who have held opinions and lifestyles at variance with what was thought to be normal and acceptable by the ruling poweres, including public opinion

Whilst the word 'episteme' has been used in English as long as the Greek classics have been studied, there is no entries for the word in the major English or French dictionaries. They all however, have an entry for the derivative word 'epistemology'.

Footnotes

1. Aristotle (384-322 BC) distinguished between five virtues of thought: epistêmê (knowledge), technê (art, skill), phronêsis (practical wisdom), sophia (divine wisdom), and nous (intellect). Epistêmê is a virtue of thought that deals with what cannot be otherwise (often a priori truths), while techne and phronesis deal with what is contingent. Back

2. Foucault first explored the processes by which ideas and attitudes are either promoted or suppressed in a society, and through the ages, in ‘Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason’, 1961.

3. Foucault, Michel 1989 (1974), ‘The Order of Things — An archaeology of the human sciences’, p.183, Routledge Classics, London & New york. Back

1. Foucault, Michel 1989 (1974), ‘The Order of Things — An archaeology of the human sciences’, p.183, Routledge Classics, London & New york. Back

2. Derrida, Jacques 1978, p.34, ‘Cogito and the History of Madness’, in 'Writing and Difference', translated by Alan Bass, Routledge & Kegan Paul. Back

3. Pinker, Steven 1997, p.4, ‘How the Mind Works’, W W Norton, USA. Back

4. Wikipedia, ‘The Order of Things’, cited 2022/09/18. Back

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Episteme#Michel_Foucault